In late February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report about two people who live in the same home in Lake County, Oregon, who were diagnosed with bubonic plague – the only two cases of the disease in the United States in 2010. Because bubonic plague is so rare in the U.S. – and potentially deadly – the victim’s county and state health departments, as well as the CDC, all participated in investigating how the patients contracted the illness. Eventually, all fingers pointed at a third member of the household: the family dog. More specifically, fleas on the family dog.

Photo by Warren Rosenberg dreamstime.com

288

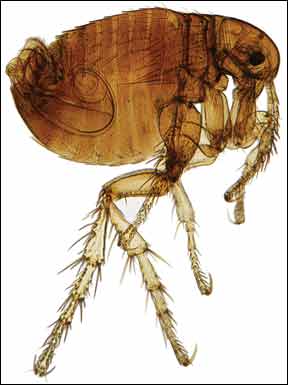

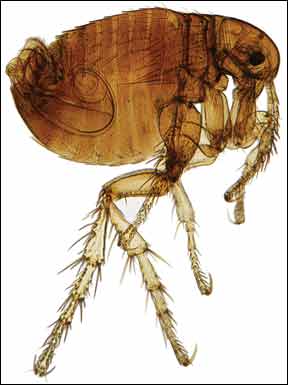

The bubonic plague is caused by a bacteria, Yersinia pestis, that is carried from host to host in the gut of infected fleas. In the United States, it’s the “rat flea” (Xenopsylla cheopis) that is the most common vector of the Yersinia pestis bacteria. Despite the name, the rat flea afflicts rats, mice, chipmunks, prairie dogs, and ground squirrels – and if its host dies, the flea will hop aboard any mammal that happens by.

Without appropriate treatment, two out of three infected humans die within six days of infection with bubonic plague.

Though the plague victims in Oregon were not accurately diagnosed until weeks after their health crises, the antibiotics and other supportive care they received saved their lives. Once the diagnosis was confirmed, investigators tested the family dog, and determined that it, too, had been bitten by an infected flea and had recovered (on its own) from a Yersinia pestis infection.

A number of press reports mentioned the fact that the dog slept on the bed of one of the family members and hinted that dogs should not sleep with humans; most of the reports also recommended that dog owners run out and buy flea collars for their dogs. Flea infestations cause far more common hazards – to humans and dogs – than the plague. Flea control should be a top priority for every dog owner, but flea collars have been largely replaced with more effective treatments.

– Nancy Kerns