I’m using this space in a novel way this month: as both an editorial and an article. Usually, my editor’s note is confined to this page alone, and is comprised of my personal thoughts, opinions, and notes about dogs and about what’s in this issue. This month, my personal thoughts and opinions about something I learned recently (having to do with the “complete and balanced” claims that appear on the commercial foods we all feed our dogs) have led me to the conclusion that WDJ needs a drastic overhaul of its dog food reviews. The explanation for that decision, and describing how our reviews will change, can’t fit on this page, nor even this page and the next one! So, I’m breaking the usual format this month, and giving you opinions and facts about pet food companies and what they have to do to represent their products as “complete and balanced.”

I won’t beat around the bush. Here’s the fact I learned recently that completely astonished me: Pet food companies don’t have to prove that their products contain the minimum amounts of all the nutrients that are considered essential for dogs before labeling and selling their foods as “complete and balanced” diets. In fact, in all likelihood, some of the products on the market today – perhaps your dog’s food? – may not meet some of the legal requirements of a “complete and balanced” food, even though their labels say they do.

To help you understand how this is possible, I have to dive into a lot of facts, and explain some things about the pet food industry and how the whole notion of “complete and balanced diets” is legally defined and regulated. So, here is the “article” part of the editorial/article.

The Association of American Feed Control Officials: What It Is and Isn’t

A national advisory group, the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO, pronounced to rhyme with “laugh-coe”), is responsible for creating and overseeing the evolution of the standards and definitions that are used to guide the players in the pet food industry.

It’s important to understand that AAFCO is not an enforcement agency in any way; by its own description, it “provides a forum whereby control officials and industry meet in partnership” to address animal feed (and pet food) standards and regulations. State feed regulators are voting members of the group, but it invites input from pet food industry participants, veterinary nutrition experts and researchers, and even (recently) consumer representatives.

Pet food is regulated by the feed control officials in each state, and each state’s feed control officials may adopt regulations unique to their own states. However, for the most part, AAFCO’s “model” guidelines and definitions for the regulation of pet food are uniformly adopted by each state.

Defining “Complete and Balanced” Dog Food

Over decades, AAFCO originated and continues to refine the description of what constitutes “complete and balanced nutrition” for dogs. The AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles, incorporating decades of canine nutrition research, establish minimum (and a few maximum) values for the nutrients that are known to be essential for dogs at various life stages. As per AAFCO rules, the “life stage” of the intended recipient of any food must be stated on the label. The canine life stages that may be referenced are:

- Adult maintenance

- Gestation/lactation

- Growth

- All life stages (this one would indicate the food meets the requirements for all of the preceding life stages)

The profiles are occasionally changed when new research prompts needed updates. For example, recent research has led to the reduction of the maximum amount of calcium that will be allowed in dog foods that may be fed to large-size puppies (those who are expected to mature to more than 70 pounds as adults). This change was published in the 2016 AAFCO Official Publication and will be reflected in formulation and labelling changes over the next two years.

Assessing the nutritional content of a food is just one method that AAFCO allows to substantiate a “complete and balanced” claim. There are actually three ways that pet food companies can substantiate a “complete and balanced” claim. The three methods are:

1. Feeding trials

2. A “family product” claim

3. Nutrient levels

Let’s look at each of the methods used to substantiate the nutritional adequacy claims.

1. Dog Food Feeding Trials

In feeding trials, a prospective product is fed as a sole diet to a population of dogs for a given length of time, while the dogs are monitored for various indicators of health. If the product sustains the test dogs for the requisite period of time, with various parameters for the test dogs’ health being met (such as the maintenance of certain blood values, and no weight loss), the product can be labelled with the claim, “Animal feeding tests using AAFCO procedures substantiate the (name of product) provides complete and balanced nutrition for (name of dog’s life stage).”

Note that the products that use a feeding trial claim don’t have to meet the parameters established by the AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles. They sustained the dogs; the dogs didn’t decline in health or weight; that’s it.

An “adult maintenance” trial lasts at least 26 weeks. A “gestation/lactation” trial must start before female test dogs come into heat, and continues through breeding and pregnancy; the test is concluded when the puppies are four weeks old (so the test is a minimum of 13 weeks). For a “growth” trial, puppies no more than eight weeks old (at the start of the trial) are fed the product for a minimum of 10 weeks.

For an “all life stages” claim, the food must be used as a sole diet in a gestation/lactation trial, followed sequentially (with the same test puppies) by a growth trial.

Feeding trials are expensive to conduct – about $20,000 per food per “life stage.” Feeding trials are routinely conducted by the largest pet food companies, but are not commonly undertaken by smaller companies.

2. Family Member

For this method of substantiation, a prospective diet is shown to be “nutritionally similar” to a lead product that passed a feeding trial. The nutritional similarity of the family product must be established by AAFCO’s “procedures for establishing pet food product families.” If this can be shown, the food is permitted to be labelled with the claim, “(Name of product) provides complete and balanced nutrition for (dogs of named life stage) and is comparable in nutritional adequacy to a product which has been substantiated using AAFCO feeding tests.”

In our view, this is the weakest of the three methods of substantiation. The products labelled with this claim are neither tested with a feeding trial, nor do they have to meet the AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles.

3. Nutrient Levels

This is the most common method used to substantiate the nutritional adequacy of foods made by smaller companies, including almost all – perhaps all? – of the ones that make the sort of foods we like. And now we are getting to the nitty-gritty.

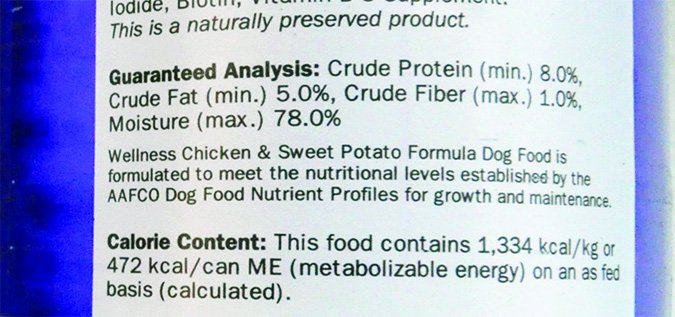

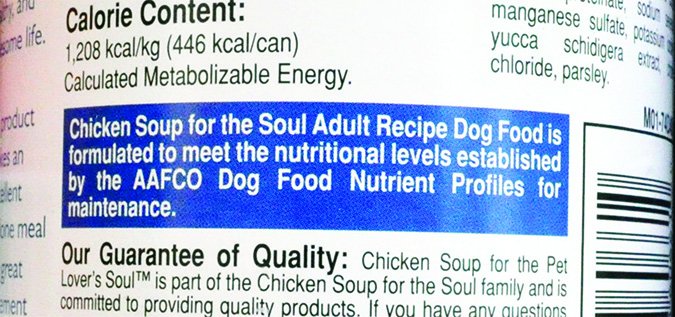

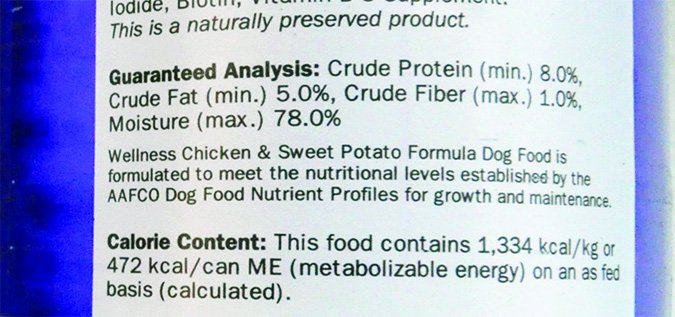

If a company uses this method to substantiate that its products are complete and balanced, it will state on the label, “(Name of food) is formulated to meet the nutritional levels established by the AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles for (name of life stage).”

The AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles establish minimum values – and a few maximums – for the nutrients that are essential for dogs. Minimum values are given for crude protein (as well as all of the constituent amino acids required by dogs); crude fat (as well as the constituent omega-6 fatty acid, linoleic acid); and the 11 vitamins and 12 minerals for which there is a consensus of current scientific evidence to support their designation as essential for dogs.

There are actually two AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles: one for “adult maintenance” and one for “growth and reproduction.” They are very similar, but the minimum amounts of protein, fat, calcium, phosphorus, sodium, and chloride in the growth/reproduction profiles are higher than the minimum values in the adult maintenance profiles. If a nutritional adequacy claim references “all life stages,” the product must meet the minimum nutrient values in the growth and reproduction profile.

No Proof!

Until recently, I was under a false impression – and no pet food company representative hastened to correct it! I thought if a food had a “nutrient values” claim on its label, its maker would have to submit proof that the food inside the can or bag actually contains nutrients in the required amounts. I guess I assumed the products would be tested by third party laboratories and the results would be filed with state feed control officials.

I was wrong.

The actual requirement is this: A company representative must sign and have notarized an affidavit that states, “This product meets the nutrient levels established in the AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles for (growth/reproduction, maintenance, or all life stages).” And then they have to keep a copy of that affidavit.

That’s it. Seriously.

No lab test results or analysis of the nutrients confirming that the statement is true are required.

And the affidavit doesn’t even get filed with the state! It just has to be kept “on file” in the company’s own files!

No kidding: The company has to, in effect, pinky swear that their products meet the required nutrient levels. And consumers have to just trust that the products do.

Editorial: I don’t think that’s right. I don’t think that’s sufficient.

Why This Matters

This matters because most dogs get most (if not all) of their nutrients from commercial food. They are a captive audience, literally. They are not free to select their own foods, they can’t follow their instincts to drive them to ingredients that contain any nutrients they may be lacking. What’s more, many owners are warned by their veterinarians and other pet professionals against feeding any table scraps or “human food” to dogs. And pet food companies encourage owners to feed their products and only their products, and to use extreme caution when switching products, lest the dog explode (or something) from diarrhea (or something).

Put another way: If most dogs eat a single type of food and nothing but that food, shouldn’t their owners be able to verify that the food truly contains every nutrient their dogs need?

Raising the Bar

I’ve long believed that, for the reasons above, consumers ought to be able to ask for and readily receive a complete nutrient analysis of their dogs’ food – to make sure that the diet contains adequate (and not excessive) amounts of the nutrients that experts agree dogs need – and that was before I knew that it was possible that products that are labelled as “complete and balanced” might not be.

Last year, we surveyed the dog food companies whose products met our selection criteria and asked this question: “Do you make a complete nutrient analysis for each of your products available to consumers? If so, are the analyses available only upon request, or is this information on your website?” As it turned out, very few of the companies had nutrient analyses readily available, and some of the ones that said they had them available were not able (or perhaps not willing) to produce them.

So, this year, we sent the pet food companies whose products have been on our “approved canned dog food” list an email that said, “There will be one significant change in how we will select and present the ‘approved’ foods on our list. This year, we are asking each company to provide us with a fairly recent (within the past year) ‘typical analysis’ for each of the canned dogs foods that they offer, and we will be comparing the values with the AAFCO nutrient profiles for dogs. If we do not receive the analyses, the foods will not appear on our ‘approved foods’ list this year.”

The Results

A few companies promptly sent us what we asked for, and these companies now constitute our gold-star picks – our top-rated producers of canned foods. See the “2016 Canned Dog Food Review” for a list of these companies.

In contrast, there were other companies we didn’t hear back from. We are more than willing to give them the benefit of the doubt; maybe they didn’t receive our email? Maybe our phone message got lost? If they respond in the next few months, we will update their information here.

We heard from a few companies that said they would be happy to get this information to us, but they needed more time. So, for them, too, we’re going to reserve space in the next few issues to update their information.

Quite a few companies sent us something that’s close to what we asked for; quite a few sent us nutrient analyses of their products that were generated by computer software. Different companies use different programs to generate these analyses, but they all work in a similar fashion: The programs are loaded with nutrient values for every dog food ingredient you can dream of, and then a formula for a given dog food is entered – so many pounds of this, so many ounces of that, etc. – and the software calculates the amount of nutrients that will be in the resulting food.

Literally every company has these software-driven analyses – projections, really – of their formulas, because that’s how pet food is formulated today. The concern is, how do these projections pan out when compared to actual laboratory analysis of the nutrients?

We put this question to a number of pet food experts – including formulators and pet food company owners – and the answer was, it depends on a lot of things, including:

- How closely the food manufacturer hews to the recipe for the food;

- What software is used to analyze the recipe;

- Whether or not the software takes into account chemical reactions between ingredients that take place when the food is mixed or cooked – reactions that might cause certain nutrient values to test at different levels than the software would predict; and

- Whether the pet food company routinely tests their raw ingredients in a laboratory and enters updated nutrient values for those ingredients into the software.

All of these are reasons why computer-generated analyses might return very different values than a laboratory test of the actual dog food.

So, even though these computer-generated analyses are not exactly what we asked for, we’re going to give the companies that sent them to us the benefit of the doubt, too. For now, they still appear on the list of our “approved canned dog foods” that starting on page 8. If they, too, send us actual laboratory test results for their products, we’ll upgrade their status to our gold-star list in upcoming issues.

But we’re also giving all the companies a heads-up: Only the pet food makers that provide lab analyses of their products will appear on our list of “approved dry dog foods” in the February issue.