[Updated January 28, 2019]

In February 2010 my Border Collie, Daisy, became one of an estimated six million dogs diagnosed with cancer each year.

Chemotherapy. My stomach tumbled to my feet. The diagnosis was scary enough; how could I possibly consider chemotherapy? I had visions of a treatment worse than the disease itself.

As it turns out, my preconceptions of chemotherapy were far worse than its reality. Chemo hasn’t cured my dog – more on that later – but it’s given us more than 18 months (and counting) of joyful, quality time together. It’s even given Daisy a dozen new friends and routines to look forward to, in the form of her oncologist and chemotherapy technicians and the special things they do to make her comfortable on her “chemo days.”

Chemotherapy for Dogs: Basics

Chemotherapy at its most basic definition is simply chemical treatment of an ailment. In this sense, we use chemotherapy everyday: antibiotics, NSAIDs, vitamins, herbs. Chemotherapy for the specific treatment of cancer involves infusing the dog’s system or a specific place in the dog’s body with cytotoxic chemicals in an attempt to destroy the cancer cells while hopefully doing as little damage as possible to normal healthy cells. Other than a few specially designed drugs for a couple of specific cancers, chemotherapy drugs attack cells in the process of rapid growth or division.

Cancer chemotherapy was developed in the 1940s when researchers became aware of the effects of mustard gas, which was being used as a chemical warfare agent. Those exposed to the gas were found to have very low white blood cell counts and researchers reasoned that if the chemical had an effect on the rapidly growing white blood cells, it might have a similar effect on the fast growing cells in some of the blood cancers. This led to further research and development of similar drug protocols.

Daisy has transitional cell carcinoma (cancer of the bladder). It is not curable, but it is treatable. I had to ask myself why I would treat her with toxic drugs. For this type of cancer, the first reason is to prevent metastasis – the spread of cancer to other parts of the body. The second reason was to control the disease and thereby increase her longevity and enhance her quality of life. For other types of cancer, chemotherapy might be used to reduce the size of the tumor so that surgery can be performed. Chemotherapy can also enhance the effectiveness of other cancer destroying treatments such as radiation. In some cases, it can rid the body of the disease, though this goal is not realistic at this time for many with the disease.

The goal of chemotherapy drugs is to kill the cancerous cells, while administering a dose that causes “tolerable” harm to the body’s normal tissues. Since a distinct trait of cancer cells is that they grow at a faster rate than most normal cells, chemotherapy agents usually affect the process of replication of these rapidly dividing cells by interfering with DNA or RNA at the cellular level. Most agents kill cancer cells by affecting DNA synthesis or function, a process that occurs during the cell cycle. The agent binds to the DNA and alters the replication process; the cellular activity is thereby halted and the cell dies. There is a balancing act between destroying as many malignant cells as possible and leaving enough normal cells to recover.

There are more than one hundred chemotherapy drugs being used to treat canine cancers and more are being developed all the time. Many years of research have resulted in established (but evolving) treatment protocols – treatment plans developed for a specific cancer type in which drugs are selected for their unique and complementary cancer-fighting properties and administered in a particular order and schedule. Combination chemotherapy is a protocol in which different drugs are rotated or given concurrently. With this approach, the drugs are given so as to attack the cancer cells in different ways thereby decreasing the possibility that the cancer cells will survive and become resistant to the beneficial effects of the agents.

There are many factors that your dog’s oncologist will take into account when selecting the protocol to use for your dog, including the type and extent of the cancer, the nature of the agents, published evidence of their efficacy, any potential adverse reactions, and your dog’s medical history and overall well-being. Your dog’s breed, too, may affect the protocol; some breeds with the MDR1 mutation cannot tolerate certain chemotherapy agents. (Get a list of commonly affected breeds and a test to identify affected individuals here.) And of course, the oncologist’s own training and experience plays a part in the decision.

If an oncologist does not see a response within a certain timeframe, the particular agent may be determined to be ineffective and another protocol may be administered or the treatment halted. The oncologist may even develop a protocol that isn’t standard but is the best way to treat your dog.

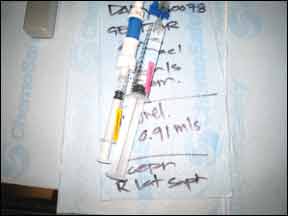

The common routes of drug administration are by mouth (orally), or by injection, which can be given through a vein (intravenous), into a muscle (intramuscular), or under the skin (subcutaneous). These are systemic treatments that travel throughout the body to reach the cancer cells wherever they may exist. More recently, other methods have been developed to increase the local concentration of the agent at the tumor site. Such site-specific applications can direct the agents to the affected areas of the abdomen, lungs, bladder, the central nervous system, and the skin. This process can reduce the systemic effects as well as provide a stronger action of the drug at the disease location.

Your dog’s specific dosage of a drug will be generally based on his body weight; other factors include your dog’s overall health and sensitivity to drugs. The dose must be high enough to be medically effective but not so high as to cause unnecessary damage to healthy cells.

Most plans begin intensive therapy with higher and more frequent doses of the agent in attempt to beat the disease back. The duration of the protocol depends on the type of cancer, the extent of disease, and how responsive it is to the treatment; the general recommendation is to administer 2-3 doses of a particular agent before determining if it is having an effect. Treatment periods can range from weeks to years. While the sound of “years of chemotherapy treatment” may sound daunting, remember that it means the treatment is working.

In addition to the chemotherapy administration itself, other exams and tests will be performed during the course of treatment. Some tests are done to see if your dog can safely receive treatment; others, such as ultrasounds, urinalysis, x-rays, CT scans, MRIs, and scopes monitor overall health and cancer status.

A routine checkup will take place during every visit. Like a report card, the following information should be relayed: your dog’s overall well-being, medications given, any changes in eating/drinking/elimination habits, any sign of illness, change in behavior, change in tumor (if visible). Report any changes to your veterinarian’s staff, no matter how insignificant the changes may seem. Thorough awareness and inspection of your dog is your responsibility. Veterinary technicians will perform a physical examination that will include obtaining heart rate, weight, and a blood sample.

Because many agents also affect healthy cells and organs, your dog’s laboratory data will be checked before each chemotherapy administration. In addition, an assessment of the effects on organs may be performed on a periodic basis. Abnormalities in any of these values may require dose adjustments or delay of therapy.

Clinical Trials of Cancer Drugs

The identification and development of effective nevv anticancer drugs is an ongoing process. Agents with a potential for antitumor activity are evaluated in clinical trials. Many veterinary teaching hospitals run such trials. lfyou are interested in having your dog participate in a trial, ask your oncologist or check caninecancer.com for a list of links.

Weighing the Chemotherapy Option

– Is the expectation of the treatment worse than the treatment itself?

– How healthy is my dog?

– How does my dog handle trips to the veterinarian?

– How sensitive is my dog’s gastrointestinal system?

– Do l have emotional, financial, and/or time commitment constraints that will lessen my ability to commit myself fully to my dog?

Possible Chemo Side Effects on Dogs

Every dog will be different in his or her ability to handle treatment. Some dogs will experience side effects; some won’t. Side effects tend to be temporary, spanning just the amount of time that it takes normal cells to be replaced or to repair the damage incurred from the chemo.

Canine oncologists have considerable experience with many of the standard drugs and how they affect dogs; they may prescribe medications to help prevent known potential issues. As with the administration of any drug, there can be a severe immediate reaction; this is extremely rare. This is why your dog will be monitored closely during the administration of the drug and observed for about an hour afterward. Other side effects can appear 1 to 3 days after administration and include lethargy, decreased stamina, diarrhea, nausea, and or/vomiting.

To counter the potential for nausea and vomiting, anti-nausea medication such as metoclopramide is often administered along with the chemotherapy agent or drugs such as Cerenia will be dispensed to give at home should these symptoms occur. Pepcid AC may also be suggested to prevent stomach upset. Bland diets can also help.

Guardians need to learn what the potential side effects are for the drugs their dog is receiving and how to watch for them. At times, it can be difficult to determine if a side effect is caused by the treatment or from the disease itself. Symptoms are especially difficult to evaluate during the beginning stage of treatment when there is nothing to compare them to. A day or two of nausea or a vomiting episode or two is not unexpected and is rarely dangerous. Notify your veterinarian immediately if your dog does not eat or drink for one day or longer, or if vomiting is continuous and water cannot be kept down, or if you notice blood in vomit or diarrhea. Record and report all your observations to the oncologist. If your dog does have a reaction, you may wonder whether to continue treatment; remember that the dosage can be adjusted or a different drug selected for use.

Unfortunately, the treatment drugs cannot distinguish between cancer cells and non-cancer cells. As a result, the destruction of the fast growing cells of the bone marrow and gastrointestinal tract becomes a concern. In addition, some drugs may damage the reproductive tract (not a problem in neutered or spayed dogs); others may affect specific organs such as the heart, liver, and/or kidneys and thus require frequent monitoring.

Some chemotherapy drugs affect the bone marrow, thus affecting the body’s ability to produce new white blood cells (WBCs). Your dog’s WBC count will generally be at its lowest 5 to 7 days after treatment. The lowering of the white blood cell count can make your dog more susceptible to infections, which generally arise from bacteria that normally live in the dog’s intestinal tract and on the skin, not from the environment. (So let your dog do the things he or she usually does, just use common sense and avoid known hazards such as dog parks with an outbreak of a contagion). Your veterinarian may also prescribe prophylactic antibiotics to prevent the possibility of infection if your dog’s neutrophil (a component of white blood cells) count is low (neutropenia), even if there is no evidence of infection.

Early detection of infection is important so that antibiotic treatment can be started immediately. Signs of infection can include loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, or depression. To help monitor for infection, familiarize yourself with how to take your pet’s temperature. Contact your vet immediately if the temperature is higher than 102.5°F (or otherwise indicated by your veterinarian), as a fever is an indication of infection. A dog’s normal temperature is about 100.5°F to 102.5°F. Again, severe vomiting or diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, or lethargy are indications you should contact your veterinarian immediately; severe infections may require hospitalization for intensive supportive care.

The cumulative effects of multiple doses of certain chemotherapy drugs can cause permanent side effects; if the risks outweigh benefits, treatment should be discontinued. Certain powerful drugs can only be used a limited number of times before the risk of toxicity to certain organs becomes too great. Other drugs may be inappropriate because of reactions or debilitating side effects. Sometimes, the cancer develops a resistance to the drug. The list of effective chemotherapy agents may diminish as treatment progresses; this is where the knowledge, experience, and creativity of your dog’s oncologist come in.

Does Fur Fall Out During Chemo?

The first question many people ask about canine chemotherapy is whether the dogs lose their hair! Most breeds have fur, not hair, and it grows and sheds in a cycle, not continuously. However, some curly-coated breeds with hair (such as Poodles) may experience hair loss. Chemotherapy drugs target fast growing cells (like hair); fur is not a fast growing cell. Sometimes dogs will lose their whiskers and shaved areas may not regrow as quickly, but that’s about it.

Find out how else chemo for dogs is like chemo for humans here.

Living with a Dog Undergoing Chemotherapy

As with humans being treated with chemotherapy, people and pets are not thought to be at risk from living and interacting with a chemotherapy-treated dog. Most chemotherapy drugs clear the system through the urinary and/or intestinal tract within 48 to 72 hours of administration. To limit exposure of these drugs to yourself and other pets, try to have your dog eliminate in one particular area, away from areas where children play and other pets frequent. Wear disposable gloves to pick up feces immediately and place in a plastic bag and seal before disposal. If possible, thoroughly rinse areas of elimination with running water to dilute any chemical residue.

If your dog vomits or eliminates in the house, wear disposable gloves and use paper towels to clean up as much of the waste as possible. Again, bag the gloves and soiled paper towels before disposing. Depending on the location of the accident, you may want to use a thorough water rinse to clean the area. If your pet is receiving daily doses of a drug that you administer orally, the drugs should be handled only while wearing protective gloves (and kept out of the reach of children and other pets). Always wash your hands after handling medications or waste! If any member of the household is pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or immune-compromised, she should not handle any treated animal’s waste or anti-cancer medications.

Paying for a Dog’s Cancer Treatment

Chemotherapy treatment can be expensive as it involves professional time and expertise, the high costs of the drugs themselves, the duration of treatment, the associated procedures and diagnostics, as well as the removal of biomedical hazardous waste (including the leftover drugs, the catheters and needles used to deliver the drugs, the technicians’ smocks and gloves, etc.). Most veterinary centers will bill per treatment, not in one lump sum. If you have pet insurance, check your policy; some plans cover treatment. CareCredit also offers special financing for approved veterinary procedures. On her blog, Dr. Nancy Kay has a great resource page for “Financial Assistance for Veterinary Care.” This information also appear in her book, Speaking For Spot. Ask for an estimate of expected costs so that you can evaluate the financial impact and discuss any financial concerns you have with your veterinarian so that he or she can offer the best treatment options based on your budget.

Questions About Chemo to Ask Your Vet

1. What is the life expectancy without treatment?

2. What is the gained life expectancy with treatment?

3. What chemotherapy agents will my dog be given?

4. How are they administered?

5. What is the process?

6. How is the effectiveness evaluated?

7. How frequently will treatment be given?

8. How long will my dog receive treatment?

9. What is the estimated cost of treatment?

10. What side effects might my dog experience?

11. What clinical signs should I be concerned about?

12. What signs require me to bring my dog in immediately for examination?

13. Who should I contact after office hours if my dog has symptoms that worry me?

Supporting Chemo Recovery

Your dog’s body must work harder to maintain good health; not only is it battling a disease, it is working to repair the collateral damage from the chemotherapy agents.

Be especially aware of symptoms of pain; as we know, dogs are especially good at hiding any signs that they might be hurting. But pain can cause stress and stress can be detrimental to your dog’s overall health and healing process. Work with your veterinary team to prevent and treat it.

The presence of cancer can result in significant alterations in your dog’s digestion. There are some general concepts that can be followed to provide good nutritional support: provide a variety of foods that are aromatic and tasty; minimize the feeding of simple carbohydrates (starches and sugars – studies have shown these to be fuel for cancer); give foods with high quality protein sources; and consider the addition of omega 3 fatty acids. While optimal nutrition is ideal, it may come down to feeding whatever your dog will eat. There are a myriad of supplements that claim to be of benefit, but many of these are unfounded and unproven; discuss any supplements that you consider giving your dog with the oncologist.

If your dog is on chemotherapy for any period of time, you may find she needs non-cancer treatment or medications. While on chemotherapy, no regular vaccinations should be given, though heartworm and flea preventatives can be given as long as not contraindicated with the chemotherapy or your dog’s overall health. Always coordinate regular veterinary care with your oncologist.

Other areas of support you might want to consider include acupuncture, chiropractic, herbal, and homeopathic remedies. Daisy receives acupuncture twice a month and takes herbal supplements as prescribed by her holistic veterinarian, who works closely with her oncologist to check for drug interactions. Her herbal supplements are ceased 24 hours before and after chemotherapy administration to reduce the potential for any interactions.

One of the most important aspects of treatment is to maintain a positive attitude and keeping your dog’s life – and your life – as normal as possible. Exercise within your dog’s abilities, play, and enjoy every moment. While we have to remember the clinical reality, it’s best to focus on your dog’s reality!

Be Your Dog’s Advocate

– Be an informed guardian.

– Research your dog’s specific disease.

– Discuss your findings with your dog’s oncologist.

– Join or start an online support group.

– Record every detail about your dog’s behavior during treatment.

– Act quickly if immediate medical attention is needed.

– Familiarize yourself in advance about the potential side effects.

Living for Today, Preparing for Tomorrow

Chances are there has been research and studies (try searching online using Google Scholar) on your dog’s particular kind of cancer. These studies will often include statistics such as median survival times and side effects of particular agents. They can be disheartening or encouraging. Do discuss your findings with your dog’s oncologist, but remember there is no crystal ball to predict how your dog might react or respond. Each dog is unique and each cancer that develops is unique. A disease that develops in one dog may not be treatable in another for a variety of reasons such as location of disease, the dog’s age and health, and the cost and availability of treatment. That said, it can be helpful to review the statistics, however extensive or limited, and use them as guidelines for weighing potential risks and benefits.

Realistically, there are few cancers that can be cured by chemotherapy. Some can go into remission (no detectable evidence of the disease), and even multiple remissions (such as with lymphoma). Others can become static (reduction and or no advancement of the disease).

Remember, if you decide to embark on the chemotherapy route, you can stop at any time. When I started treatment with Daisy, my guiding principle was that if it affected her quality of life in any way, we would cease therapy immediately. She’s been receiving chemotherapy for over 16 months now, including intravenous mitoxantrone, carboplatin, and vinblastine; we also tried the oral drugs Leukeran (chlorambucil) and Palladia. Unfortunately none of these had the desired effect of combating the disease, but fortunately they did not have any detrimental affect to her well being. She’s also received piroxicam (an NSAID that has anticancer properties) for over a year; we’re not sure if this had any effect on the disease, but it did seem to have a palliative effect (she now takes Deramaxx instead).

There was a period when I did stop treating her with conventional chemotherapy agents, but that was because we had run out of drug options for her particular type of cancer. At that point, I put her on an herbal chemotherapy as recommended by her holistic veterinarian. She continues taking it now in conjunction with a special combination protocol of two chemotherapy agents as developed by her oncologist. We’re now at 18 months since diagnosis (her prognosis was less than a year) and I can joyfully report that her disease is static and she is happy and feisty. She comes home from her oncology visits ready to play frisbee.

The author wishes to extend her heartfelt thanks to Daisy’s amazing and caring oncologists, Jeffrey N. Bryan, DVM, MS, PhD, DACVIM (Oncology), at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri and Martin Crawford-Jakubiak, MLAS, DVM, DACVIM (Internal Medicine, Oncology), and his wonderful team at Sage Centers for Veterinary Specialty and Emergency Care in Concord, CA.

Author Barbara Dobbins is a dog trainer on hiatus who has been inspired to return to school to study veterinary oncology.

Dear Ms. Dobbins,

My female Pembroke Welsh Corgi was diagnosed with transitional cell carcinoma in May 2018, when she was 12 yrs old . She had surgery to insert a urethral stent, and then had several months of chemotherapy with vinblastine and then mitoxantrone. I chose to do that to prolong her quality of life as long as possible (I was told that chemo could extend her life by 6-9 mos.) It is noteworthy that she had no noticeable negative side-effects from chemotherapy. I declined radiation because that would have required treatment out-of-town almost every day for a month, and I could not bear to be separated from her that long; nor did I think it would be in her best interests to be separated fro me for that long, or to be put under general anesthetic almost every day for a month.

Sadly, Katie’s scans in May 2019 showed that her cancer had metastasized significantly in the three month since February, and her oncologist at the OVC in Guelph, Ontario could offer nothing more than palliative care. I was told that she had 2-4 weeks left. Exactly 4 wks later, Katie experienced a significant decline in her quality of life, such that I had to let her go to save her suffering 4 days later. That was two weeks ago, and I am still grieving the loss of my little girl at age 13.

I wish to say that I believe chemotherapy was the correct choice for Katie, as it gave her another year of good quality life. The end came very quickly, and I admit that took me by surprise. I know only that I did everything I could to help my little girl, and that – as with my first dog – pet insurance is essentially a joke when it comes to payouts.

I hope that Katie’s story will help shed some light on your article on chemotherapy from a “mother’s” pov, and thank you for writing the above article.

Thank you both for the information. I’m so sorry for your baby.

Our boy, Princeton, was recently diagnosed with TCC on June 21, 2019.

We are just embarking on this journey. At the time of diagnosis, his cancer was contained to the bladder with no local or distant metastasis. I’ve had to wait 3 weeks to get him into the University of Florida’s veternary oncology group. I’m afraid of what may have progressed in 3 weeks. The only med he’s on right now is Piroxicam. He’s 13.5 years old. I don’t know exactly what to do. I don’t want to make him sicker. I was grateful to hear that your pups didn’t suffer terrible side effects. If you have any other insight please let me know.

Our dog Mack was diagnosed with bladder cancer in January 2019. We have gone through the same chemo regimen as outlined by the author. The difference is, Mack has had chronic pancreatitis for at least 5 years now. He is currently on the chlorambucil/Palladia combo and the Palladia really kills his digestive system. He is gassy and gets bad diarrhea. His quality of life isn’t good in the days following Palladia. I’m curious as to what the author ended up using for Daisy? The chemo drugs used and also the homeopathic treatment. We feel lucky to have Mack alive 9 months later, but would love to see his qualify of life improved if possible.

This was very helpful and heartening. Our 5.5 year old Pembroke Welsh Corgi was diagnosed with TCC about a month ago. Surgery was attempted, but the tumor cannot be removed. We started carprofen immediately, and she starts mitoxantrone tomorrow. I am so anxious about the side effects, but this information gives me confidence that we have made the right decision.

We also have a Pembroke Welsh Corgi that was diagnosed with TCC bladder cancer. I saw the two replies from other Corgi owners and wonder now if it is becoming prevalent in this breed also. Our little Marla’s tumor was found off chance in a routine checkup in June,2018. We were fortunate to have close specialist facilities, and a week later a more detailed ultrasound was performed and a BRAF urine test confirmed TCC. We were told surgery was an option, but due to other personal circumstances, and knowing our Marla’s temperament, we decided not have it, and opted for Chemo, mitoxantrone, and the NSAID, carprofen. She gets chemo every three weeks. It took a few sessions to get the dosage right, her white blood cell count was too low after the first treatments, but she had no noticeable side effects from the chemo itself. She is just our crazy little Marla 🙂 We are lucky her tumor is not in the trigone area. It has now been 16 months since her tumor was first found, 15 months of chemo, and it has not grown noticeably and is considered stable for now. The only problem we have now is a recurring urinary tract infection which was scary because she was having blood in her urine, but it is the UTI, not the cancer causing the blood. The oncologist said that the cancer makes the UTI more prevalent. We have been dutifully taking her every three weeks, but as I said before, we also had a lot going on, plus we both work full time. I feel bad not having researched as much as I could, but recently finally had time to look more, and I was wondering how long any dog has survived with TCC. Our oncologist was always hard to talk to, and we mostly interacted with the vet techs. We made the very hard decision to change oncology vets, which, again, we are very fortunate to even have the choice to go elsewhere. Our new vet says as long as the chemo is keeping her tumor from growing, we will continue with the same treatment, and if it does start growing, told us of other treatment options. Marla was 10 when she was diagnosed, and is now 11 plus. She doesn’t even seem to know she is sick. She has grown to not like going to the vet, and we have troubles getting her to go in the car, so I think she is getting tired of getting the IV put in her. We’re hoping the changing of vets might help. Marla loves attention, and this place seems to give more personal attention, rather than just treatment. We just try to enjoy the time we have with her while she is still with us.

I think this article should have highlighted the anticipated lifespan for dogs that undergo chemo as what I have experienced myself and seen elsewhere in print that dogs with cancer and then chemo typically live up to 10 to 12 months longer with a significant share not extending their lives at all.

Therefore given the emotional toll on you and your dog in addition to the expense question is whether it is always worth it. Your vet if they are honest will be good point of reference whether it is worth it in your specific situation depending on the age and overall physical condition of your dog in addition to type of cancer and how far advanced.

Everyone…literally everyone…I know who has done chemo for their dog regretted it because it came at a high price both emotionally and financially without significantly extending the dog’s life. I think that should be highlighted as a consideration.

Is it ok to give herbal supplements when on palladia?