We recently had our new Cardigan Welsh Corgi spayed. When we picked Lucy up from the vet hospital, we were handed an instruction sheet that included the dreaded phrase, “Restrict activity for 10 to 14 days.” In the few short weeks that this little dynamo had been a member of the Miller family, I had already realized how difficult it would be to keep Lucy under wraps.

We were lucky that it was only 10 to 14 days. Many canine injuries and ailments require much longer incarceration. Our 75-pound Cattle Dog mix had knee surgery (a tibial plateau leveling osteotomy – TPLO) several years ago. We had to keep Tucker quiet for a full six weeks following his operation! Fortunately, he was older and more settled than our adolescent Corgi, and our vet supplied us with tranquilizers to keep him quiet for the first few days, but it was still a large-scale challenge.

What do you do when your vet tells you your dog can’t run around for a period of time? You get creative. You can, of course, arm yourself with an endless supply of stuffed Kongs and other such interactive toys, but even those get old after a while.

You can, and should, use calming massage techniques to help your dog adjust to confinement, but that’s rarely enough.

You can beg your vet for tranquilizers (for the dog, not for you!) and she may give you a few to get you through the first critical days of a leg repair or other major surgery, but probably not enough to get you off the hook.

Eventually, you’re likely to have to do something to tire your dog out. The good news is that mental gymnastics can be just as tiring for a dog as physical exercise, and if can keep your dog’s brain occupied, you can make it through the torture of “restricted activity.”

Practice Free-Shaping Behavior Training With Your Dog

Canine incarceration is the perfect opportunity to introduce your dog to some free shaping exercises. Shaping is the process of taking a complex behavior and breaking it into little pieces, then marking and rewarding each piece until you work up to the whole behavior.

With free shaping, you do no luring whatsoever. You simply take a behavior that the dog offers you and gradually shape it into something by marking (generally with an audible marker such as a click! of a clicker or an exclamation such as “Yes!”) and rewarding increasingly large, intense, or extended examples of the behavior. You can use this method to mark any behavior your dog happens to engage in – a sneeze, a blink, a yawn, putting his ears up or down – and put it on cue.

Free shaping has several benefits in addition to exercising your dog’s brain. It teaches you to be patient, gives you a real opportunity to watch your dog think and solve problems, and it encourages your dog to offer behaviors.

You have to be a bit of a student of animal behavior to appreciate free shaping. I never introduce it in my “basic good manners classes,” since most dog owners need to be committed to training beyond basics in order to have the patience and understanding to do this. If you are a Whole Dog Journal reader, you probably are committed, so let’s get started!

Shaping Exercises to Try with Movement-Restricted Dogs

Here is a good exercise for dogs who are on total restriction. Your goal is to get your dog to offer one of these behaviors on cue – Nose Lick, Head Turn, Ear Flick, or Paw Lift – without any luring or prompting on your part. Here’s how:

• Sit on a chair with your dog in front of you. If he wants to jump on you, put him on a tether and sit just beyond his reach.

• Wait for him to offer one of the four behaviors.

• When he does, click (or use some other reward marker, such as a mouth click or the word “Yes!”), and then quickly give him a treat. Once you have clicked and treated one of the four behaviors, stay with that one; don’t click and treat randomly for any of the other four.

• Wait for him to repeat the chosen behavior. When he does, click and treat.

• Keep doing this until you see him start to offer the chosen behavior deliberately, in order to make you click and treat.

• Put the behavior on an “intermittent schedule of reinforcement.” That is, click and treat most head turns, but occasionally skip one, then click (and treat) the next offered one. Gradually make your schedule longer and more random by skipping just one more frequently, and sometimes skipping two, then four, then one, then none, then three – so your dog never knows when the next one is coming.

This makes the behavior very durable – resistant to extinction. Like playing a slot machine, your dog will keep offering the behavior because he knows it’ll pay off one of these times! It’s important to put the behavior on an intermittent schedule before raising the shaping criteria so he doesn’t give up when you are no longer clicking each try.

• Decide if the behavior is fine as it is, or if you want to shape it into something bigger. A Paw Lift, for example, can be shaped into Paw On Your Knee, Shake, High Five, or even Salute. Head Turn can be shaped into a Spin. Ear Flick could become Injured Ear, while Nose Lick might become Stick Out Your Tongue.

• Determine the “average” response your dog is giving you. If you want to shape Head Turn into Spin, envision a 360-degree circle around your dog. Perhaps your dog is offering head turns anywhere from 5 degrees to 75 degrees, but the average is 45 degrees. Now you are going to click and treat only those head turns of 45 degrees or better.

Over time, your dog’s average will move up as you click only the better attempts. When that happens, raise your criteria again – perhaps it was a range of 30-95 degrees, and now you’ll click only those head turns that reach 60 degrees or better. Keep raising the criteria – gradually, so you don’t lose your dog’s interest – until you have a complete Spin.

• Now give it a name (Spin!) and start using the verbal cue just before your dog offers the behavior. Eventually you will be able to elicit a Spin with the verbal cue – all by free shaping.

You can figure out how to do this with the other three behaviors. If your dog has to be kept confined for a long period, you might have time to teach all four, one after the other. Lucky you!

Games to Play with Movement-Restricted Dogs

There are a number of other low-activity games you can play with your shut-in dog, such as:

• Targeting/object discrimination. Teach your dog to “Target” on cue by giving him a click and treat every time he touches his nose to a designated spot, such as the palm of your hand or the end of a target stick. As soon as he can do that easily, add the cue “Touch!” just before his nose touches your hand (or the stick).

When he will target on cue, transfer the targeting behavior to an object, by holding the object in your hand and asking him to “Touch.” When he’s targeting well to the object, give it a name: “Bell, Touch!” or “Ball, Touch!” When he knows the names of several different objects, you can have him pick out the one you ask for.

• Take It. This behavior is a piece of the retrieve, but you can do it without the run-after-and-retrieve part. It’s also useful for teaching your dog to pick up dropped items and carry things for you. Just show your dog something you know he’ll want – like a treat or a favorite toy – and ask him to “Take It!” Odds are he will, happily. When he’s good at taking his favorite things, try a slightly less-beloved toy, and work your way down to non-toy objects. Click and treat each “Take It!” When he’s good at “Take It!” you can gradually extend the amount of time before you click and you’ll begin teaching him to “Hold It!”

• Give. This is also part of the retrieve, and is useful for getting your dog to let go of “forbidden objects” without a fuss. Give your dog something he’s allowed to have and that he likes a lot, like his favorite toy. Then offer him a handful of yummy treats and say “Give!” When he drops the object to eat the treats, pay them out slowly and pick up the object with your other hand while he’s occupied eating. Then, when he looks up, say “Take It!” and give him back the object. Double bonus – he gets the yummy treats and he gets his toy back!

Practice this until he’ll give up the object on cue. Next time he gets his chompers on a forbidden object, play the “Give” game and he’ll give it up without playing keep-away. (Note: If your dog is a resource guarder, this may not be a safe game to play. In that case, you’ll need to modify the resource guarding behavior first.

• Leave It. This game teaches your dog to take his attention away from something before he has it in his mouth.

Start with a “forbidden object” that you can hide under your shoe, such as a cube of freeze-dried liver. Show it to your dog, say “Leave It!” and place it securely under your foot so he knows it’s there but can’t get it. Let him dig, chew, and claw at your foot to his heart’s content (wear sturdy shoes!) until he loses interest. The instant he looks away, click and treat. As long as he’s not trying to get the liver, keep clicking and treating. This is called “differential reinforcement for any other behavior” (DRO) – you are rewarding any behavior other than trying to get the treat.

When he’s leaving your foot alone, uncover the liver cube slightly, and continue your DRO. If he tries to get the treat, just quietly (but quickly!) cover it back up with your foot and wait for him to remove his attention again.

When he’ll reliably leave liver on the floor and he’s ready for more strenuous activities, generalize the behavior to other situations by using a leash to gently restrain him from real-life temptations while using DRO to reward him as soon as he removes his attention from the cookie in the toddler’s hand, the ham sandwich on the coffee table, or the dog on leash on the other side of the street.

• Puzzle Games. There are a number of interactive toys on the market that require your dog to think and perform a mechanical puzzle-solving skill. Unlike stuffed Kongs and Buster Cubes, your dog will need your active participation with these games. As soon as he solves the puzzle, he’ll need you to put the toy back together so he can do it again. They are great fun, and one more way to encourage your dog to quietly think and tire his brain.

• Tug. Gentle games of Tug, with strict rules, may be a useful way to burn off some incarceration energy. (See “Tug o’ War is a Fun Game to Play with Your Dog.”) Check with your veterinarian first to be sure this won’t be a problem for your dog’s particular condition.

Benefits of Giving Your Dog Down Time

There are lots of other low-activity exercises and games you can play with your dog to help pass the long hours and days of restricted activity. It’s a great time to work on counter-conditioning and desensitization if he’s at all touchy about nail trimming, grooming, or any other handling procedures (see “When Your Dog Hates Being Touched.”)

You can also spend this time transforming him into a tricks champion, teach him ‘Possum, Relax, Rest Your Head, Crawl, Reverse, Speak, Count, Nod, Shake Your Head, Kisses, Hugs . . . the list is virtually endless. If the two of you put your minds to it, at the end of a six-week lay-up, or even a shorter bout of nasty weather that keeps you shut indoors, you and your dog should be very well educated!

How to Shape Your Dog’s Behavior: Cardboard Box Edition

I first heard about this brain-teasing, free shaping exercise from Deb Jones, PhD, a wonderful positive trainer in Stow, Ohio.

Have your clicker ready. You are going to click and treat your dog for any behavior related to the box. With no preconceived idea about what behavior you want, set a cardboard box on the floor in front of your dog. Many dogs will sniff a new object with interest – click and treat when he does. Then watch him closely, and continue to click and treat any box-related behavior. See what your dog will give you!

If you’re not getting a lot of box behavior, click and treat even tiny movements – looking at the box, moving toward, or even looking in the general direction of the box.

Be careful you don’t cheat! It’s tempting to “help” your dog by pointing toward the box, or moving around it. Don’t! You can help by looking at the box instead of looking at your dog, and you can stand on the opposite side of the box, but anything more than that is too much. Remember, you want your dog to learn to think – and he won’t learn if you hold his paw and show him what to do; he’ll just wait for you to bail him out.

“Crossover dogs” (dogs whose early training was force-based, and whose later training was reward-based) can be particularly slow to offer behaviors because, when they were subject to punishment for doing the “wrong” thing, they learned it’s easiest to stay out of trouble by doing nothing. Free shaping exercises are great for helping crossover dogs get over that inhibition – providing you don’t help them too much, but rather take your time and let them think things out for themselves.

When your dog offers a lot of box-related behavior, then you can decide to shape it into something “official” if you like. If you are more of a type-A, goal-oriented kind of person, this may help you make more sense of the Box game. Be willing to think outside the box, though – there are lots of behaviors your dog can do beyond just jumping in and sitting in it – although, if it doesn’t interfere with whatever physical condition your dog is recovering from, it sure is cute!

KEEPING DOGS INACTIVE AFTER SURGERY: OVERVIEW

1. Teach your dog some of the basics, like sit, down, stay, and targeting, before a lay-up, so he’s prepared to play more advanced stationary games with you.

2. When you know in advance your dog will be on restriction, stock up on puzzles and other inter-active toys well ahead of time so you’re not scrambling to find them at the last minute.

3. Install a good foundation of loose-leash walking so you can take your dog for walks when he’s ready for limited exercise, without worrying that it will be a big struggle. (See “Loose Leash Walking: Training Your Dog Not to Pull.”)

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She is also author of The Power of Positive Dog Training, and Positive Perspectives: Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.

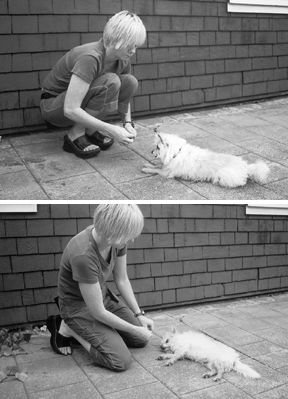

Thanks to Sandi Thompson of Sirius Puppy Training in Berkeley, CA, for demonstrating for us.

Great article! My dog is going for TPLO surgery next week so these ideas are going to come in very handy post op.

Can you recommend any specific puzzle games?

Hi,

Truly a lovely guide on “How to Keep a Dog Calm After Surgery”. Thanks for the share. This will be benefitted to all of the dog lovers. Keep writing.

Thank you very much.

Priyota Parma

Executive Consultant

DogMexico.Com