Your six-month-old puppy is scheduled to be spayed tomorrow. When you call to confirm your appointment, and review the veterinarian’s estimate of charges with the receptionist, you learn that you will be charged $60 for a blood panel. Is this necessary?

• Your five-year-old Golden Retriever seems sick. You’re observing him for any evidence of disease or injury. And yet, all you can really find is that Ralph seems “not himself.” A friend urges you to have Ralph’s blood tested . . . What for?

• Your Poodle is eight years old. She has bad breath and tartar-encrusted teeth, so you make plans to take her to a veterinarian to have her teeth cleaned. However, the doctor demands to perform a blood test before he will anesthetize her for a dental scaling. What’s that got to do with anything?

• At a recent health exam, your veterinarian asks about your 12-year-old Pointer’s activity level. You explain that the dog has begun to decline to join you on your daily jog, and chalk it up to the onset of his “old age.” But your veterinarian is alarmed, and asks to conduct blood tests. Isn’t it normal for an old dog to want some rest?

A visit to a veterinarian is imminent for each animal, even though the justification for each individual’s blood test is different. In each of the cases we’ve described, blood testing will reveal a wealth of useful information about the dog’s state of health. There are cases, however, where this information is really not needed. How can you know when blood tests will and will not repay your investment with information that is critical for tailoring a treatment plan for your dog?

You can answer the question for yourself, once you understand what blood tests can and can’t do.

What is a Blood Test?

Blood is composed of different types of cells, and the status and percentage of type of cell present in the mixture communicates important facts. There are a variety of ways to examine blood; each examination method reveals specific information. A morphologic inspection consists of looking at the shape of the blood cells under a microscope. A complete blood count (CBC) is just what it sounds like – an actual count of the various types of red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets present in a specific volume of blood. The goal of measuring blood by means of a hematocrit (HCT) or packed cell volume (PCV) is to determine the amount of RBCs.

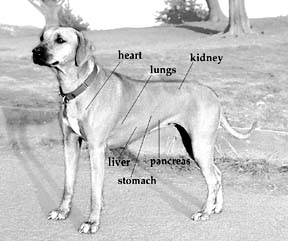

A chemistry profile identifies and quantifies other agents in the blood, including enzymes, glucose, proteins, electrolytes, cholesterol, and other substances produced by the internal organs. A “chem screen,” as it is often called, can tell a trained observer how well these organs are functioning. For example, a lack of albumin, which is produced by the liver, can alert you to decreased liver function; a high amount of amylase, which is produced by the pancreas, can indicate pancreatic and/or kidney disease. Typically, 28 different chemical values are yielded from each blood sample, and, studied together, these tests can help identify the location and severity of disease in the body.

Blood can be regarded as a rich river of information about the body. While it is possible that a dog can have health problems without any detectable abnormalities in his blood, these cases are the exceptions, rather than the norm.

When Should You Get Your Dog’s Blood Tested?

The cases described at the beginning of this article are good examples of the most beneficial opportunities to glean information about a dog’s health.

A young dog, at the veterinarian’s office for a spay or neuter surgery, should not be expected to have any health problems that would preclude anesthesia or surgery. However, veterinarians will tell you that there is one great reason to authorize the additional expense of a blood test at this time: the future. Your dog’s vigorous youth is the optimum time to establish a “baseline,” that is, a chemical picture of how she “looks” when she’s healthy. Results of these tests can be compared to those from tests taken in times of trouble to establish the extent of the deviations from her “normal.” Some veterinarians use this same rationale to request that you allow annual blood tests on your apparently healthy animal. This is undeniably a great opportunity to detect subtle signs of disease before your dog has an opportunity to display symptoms; early treatment of any disease helps prevent permanent damage.

On the other hand, if your young dog is bright-eyed, glossy-coated, and energetic, the tests may never detect anything amiss. Today’s veterinarians are taught to be assertive in encouraging owners to “make an investment in their pet’s health,” but the truth is, authorizing tests at this time in your dog’s life is entirely up to your own conscience and pocketbook. The possibility that you might discover early signs of disease is a compelling concept, but it shouldn’t be considered mandatory by any means. After all, not many of us have annual blood ourselves.

A Dog Who is “Not Quite Right”

Blood tests are very valuable in cases where a dog isn’t displaying any overt signs of disease or injury, but still doesn’t seem quite like himself. A veterinarian attending to such a dog, like the Golden Retriever mentioned at the beginning of the article, would first conduct a thorough physical exam and take a complete history. However, there are numerous cases where a blood test and only a blood test would be able to reveal the source of his subtle malaise. For example, standard blood tests might show that his red blood cells were smaller than usual, his hemoglobin levels were low, and that he had an iron deficiency. These facts would suggest that the dog may have been losing small amounts of blood through his stools over a period of time. A radiograph of his digestive tract would be indicated, and the pictures could reveal an intestinal tumor that was responsible for the blood loss.

Chem screens can also detect – if not always identify – complex problems with the endocrine system. The endocrine system is responsible for making gradual responses to environmental and internal stimuli, which are mediated by chemical substances (hormones) secreted by endocrine glands into the blood.

An experienced veterinary interpreter of the test results can read the hormonal responses that have been dropped into the blood system like clues to a crime. Thyroid dysfunction is the most frequently recognized endocrine disorder of the dog, followed by adrenal function disorders, Addison’s and Cushing’s syndromes (hypo- and hyper-adrenocorticism) which are very common in adult and aging dogs. Though these diseases may be detected early through routine periodic screenings and managed so as to improve quality of and prolong life, they are difficult to diagnose accurately without appropriate laboratory tests.

“Today, viral and bacterial diseases aren’t the main cause of death for many dogs; as with humans, dogs are living longer due to better disease control and good nutrition,” comments Dr. Fred Metzger, a veterinarian from State College, Pennsylvania. “My clinical experience demonstrates the most common diseases as renal disease, then diabetes, and third, either hypothyroidism or Cushing’s disease. Fortunately, if a client will avail himself of them, there are many clues blood tests can give us when these diseases are in progress, especially for geriatric animals.”

Other conditions commonly detected by blood work include hypercalcemia (too much blood calcium which could indicate possible tumor growth), and hypoglycemia (low blood sugar indicating diabetes). “Hypothyroidism is a common problem in aging dogs, so, starting at age seven, thyroid panels should be included in all dogs’ blood panels,” says Dr. Metzger. “Electrolytes tests are important too. For example, Addison’s syndrome (hypoadrenocortism) is frequently associated with severe hyponatremia (low sodium), but is frequently misdiagnosed by those who don’t run electrolyte panels.”

Pre-Surgical Blood Tests

The middle-aged Poodle in need of dental work is another classic candidate for blood tests. Anesthetic drugs are processed by the liver and kidneys, which also remove the drugs from the body in a more or less predictable rate. However, if the dog’s liver and/or kidney function are impaired, normal usage of anesthetic drugs can have deadly consequences for the dog.

Just as with people, as your dog ages, her organs gradually become less efficient. Holistic veterinarians speculate that the plethora of toxins that modern dogs are exposed to (from flea-killing pesticides to preservatives in commercial dog foods) speeds up the degradation of these organs, rendering them ill-prepared for the major challenge of removing anesthetic from the bloodstream.

Results of a pre-surgical blood test, specifically focused on the values that reveal the efficiency of the liver and kidney, can help the veterinarian select the safest dose and type of anesthetic drug for your dog.

Alternatively, in case of tests that reveal very poor organ function, the veterinarian may want to discuss the risks and benefits of the surgery with you, or may elect not to risk the surgery at all.

It’s impossible to say exactly when your dog’s organs are likely to start showing signs of compromised function. After all, what ages are considered “middle-aged” and “geriatric” differ widely from breed to breed.

Again, it’s ultimately up to you to decide, with input from your veterinarian. Are there any other reasons to believe your dog’s vital organs are not as vigorous as they should be? Any dog with chronic health problems is a good candidate for a pre-surgical blood test. But if your middle-aged dog is energetic, fit, and happy, you’d probably be safe foregoing the test. Do young, healthy animals need a pre-surgical blood test? This is where opinions vary wildly. Emotion and economics are what usually inform an owner’s decision. Since it IS possible, but highly uncommon, for a young dog to have as-yet undetected liver or kidney problems that could complicate anesthesia, a breeder with a valuable or rare breeding animal may consider the extra expense as “insurance.”

A veterinarian’s personality and style of practice are what generally shape his or her opinion of this matter. Aggressive proponents of the tests MAY be opportunistic, looking for a way to increase billable services, but more likely, they are medical conservatives, trying to further reduce the chances that the animal will suffer complications on their surgical table. Holistic veterinarian Dr. Jean Hofve, of Denver, Colorado, usually skips pre-surgical blood tests for apparently healthy young and middle-aged animals. “The most widely used anesthetic today, isoflurene, is quick-acting and quick to be metabolized out of the system. It is considered very safe. Older dogs should be watched more carefully for blood pressure changes while under the anesthetic, but administration of IV fluids would take care of potential problems.”

Dr. Metzger is more conservative. “This is a good time to get base-line information on the dog for future use, as well as to check liver and kidney function. The client learns something, and we have information to use and compare to if there is a medical event someday down the line,” he says. Veterinarian and clinical pathologist Joe Zinkel, of the University of California at Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, has adopted a middle-of-the-road approach. “For a young healthy animal in for elective surgery, such as spay, neuter, dew claw removal, or dental, I’d run a few, minimal tests – say, the packed cell volume to rule out anemia, and with the fluid left from the sample, a dipstick Blood Urea Nitrogen (AZO test) for a quick kidney test. With good results from these two simple tests, the practitioner can be pretty much assured that the animal is in overall good health, a good candidate for a surgical procedure.”

Blood Tests for Geriatric Dogs

As for the 12-year-old Pointer who has decided to give up jogging? Most veterinarians would advise including a blood test in any elderly dog’s annual health examination. And a dog who has begun to “show his age” with stiffness, reluctance to exercise, or depression may actually be manifesting signs of disease, rather than “age.”

Once older dogs have their health problems diagnosed and treated, their owners are often surprised to discover them return to a level of activity they haven’t seen for years.

Keeping Perspective

Aside from the cost, there is perhaps only one downside of running blood tests: the possibility that your dog’s “normal” values are not normal for the rest of the dog population, tempting a thorough veterinarian to order further diagnostic tests. Dr. Zinkel explains: “From time to time you’ll see perfectly healthy animals that may have one value out of the ballpark, giving an odd value that you may chase down to no avail.”

Dr. Zinkel estimates that as many as one out of every 20 animals may have blood values that are abnormal, without having any health problems. While he appreciates how quickly the labs are now able to return critical information back to veterinarians’ offices, he says it’s important to view the results in context. “The value of blood tests is inestimable, but the veterinarian’s physical exam, history, and other observations will always be indispensable,” he says.

My dog died of a thrombosis to her brain being spayed. She was 1year old and appeared fit and healthy. I was told she had round worm (toxocara canis) eggs in her blood causing the clot. I had found her as an abandoned animal. I was trying to find her a forever home. Should this have happened?