[Updated January 16, 2018]

Let’s be honest: Some areas of veterinary study are sexier than others. The functioning of complex organs such as the thyroid, the treatment of behavioral aberrations like separation anxiety, the risk factors for hip dysplasia – all these topics have had their share of academics willing to question, probe, and publish their findings. But anal sacs? Very few researchers in veterinary medicine find themselves called to explore the nuances of this grape-shaped pair of pouches.

Very likely this has to do with their location at the puckered inside edge of the anus, or their contents, which is an oily, semi-liquid substance that smells like a dead mackerel…on a good day.

Also dampening academic enthusiasm is the fact that there is no biological corollary in humans: Unlike some other mammals, including bears and sea otters, we humans simply don’t have anal sacs. (Conversely, dogs don’t get hemorrhoids, so maybe we’re even.) And if our species doesn’t have to contend with something so gross, why go out of your way to study it?

One good reason is that so many dogs have minor but annoying problems with their anal sacs – and some dogs have required surgery to repair or improve the situation.

What Are Canine Anal Sacs?

Many dog owners are oblivious to the existence of these two sacs, whose openings are positioned at four and eight o’clock as the clock ticks around the dog’s anus, and are not obvious to the untrained eye. In dogs, anal sacs are considered vestigial, sort of like the human appendix. When marking and defending boundaries were crucial for canine survival, they likely had a key role, adding a dog’s unique and identifying scent to his excrement; today, salutatory butt-sniffing might very well be an evolutionary remnant of that territorial imperative. Another theory is that the liquid in the anal sacs lubricates hard stool, making it easier for the dog to eliminate.

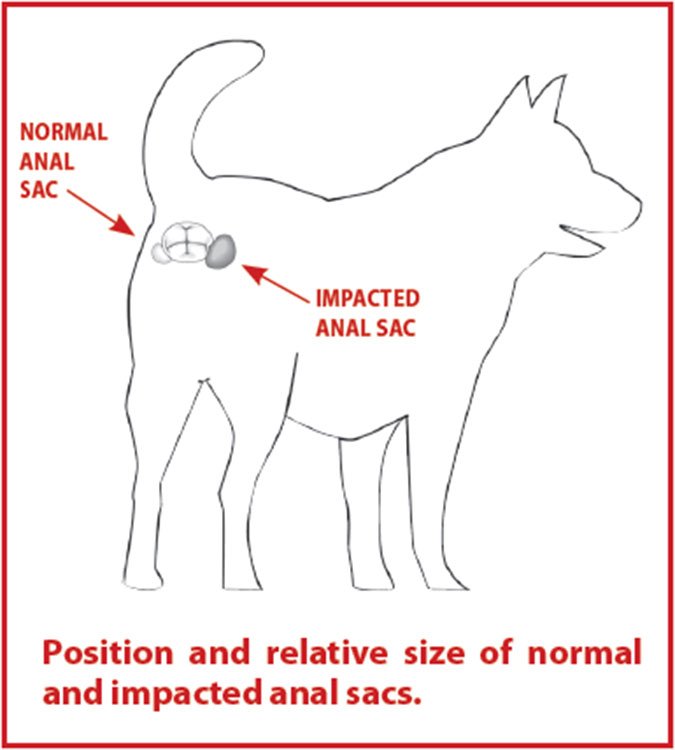

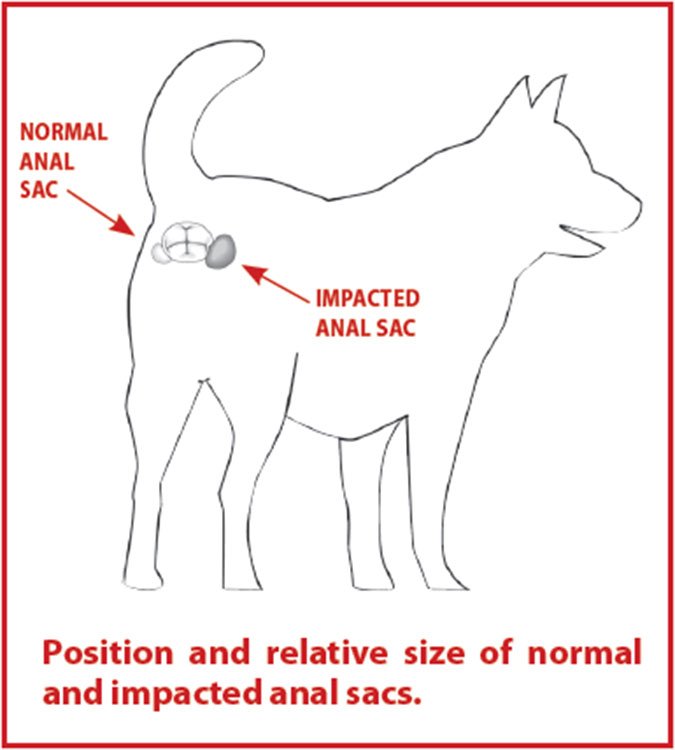

Located between the internal and external anal sphincter muscles, and lined with oil and sweat glands, each anal sac is connected to the outside world via a short, narrow duct. Occasionally, when these ducts get plugged up, anal sacs can get impacted or, if left untreated, infected, leaving the dog uncomfortable and the owner befuddled at why her furry co-habitator is now dragging his bottom across the living-room rug.

“Most people don’t know that anal sacs exist, until their dogs start scooting,” says Jennifer Schissler, DVM, MS, DACVD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences in Fort Collins.

The fact that dermatologists are the specialists under whose purview anal sacs usually fall tells you just how much of a veterinary stepchild these obscure little cavities are. “In veterinary medicine, dermatologists are a catch-all for things related to glands,” Dr. Schissler shrugs. “Nobody really is an expert in anal sacs.”

Scooting and Other Signs of Anal Sac Problems

Along with “scooting,” or dragging their rears across carpets and floors, dogs can exhibit a variety of signs of an anal-sac problem, including licking or biting at their anus; painful or prolonged defecation, or avoiding it altogether; and, in severe cases, an abscess or draining tract around the anus. (Sudden fear or excitement can also sometimes prompt a dog to empty his sacs involuntarily, which is entirely normal – and particularly nasty if he happens to be on your lap or in your arms at the time.)

A full physical examination, including a rectal exam, can determine if anal sacs are the problem. “I might do a fecal exam to see if there are any internal parasites, because tapeworms can cause perianal itch,” Dr. Schissler explains. “Flea-bite hypersensitivity can be a cause, too.”

She ticks off other sources of irritation around the rectum that may not be related to impacted anal sacs: Some dogs can have an allergy that manifests around the anus and is not an anal-sac problem at all; still others might have a tumor or polyp in the rectum or anal sac.

If all of the above are ruled out and the anal sacs are dilated and inflamed, then the veterinarian will usually evacuate (empty) them. “Some veterinarians will do cytology and look at the material under a microscope,” Dr. Schissler says. Inflammatory cells might suggest infection and a subsequent prescription for antibiotics.

Expressing Your Dog’s Anal Glands: Don’t Try It at Home

Emptying anal sacs by manually manipulating and squeezing them is not something that Dr. Schissler recommends to the average dog owner. If a dog’s anal sacs are working normally, they will express themselves on their own when the dog defecates; there is no regular need to manually empty them.

If the dog has a problem with her anal sacs that requires manual expression, some brave souls prefer to do it on their own rather than bringing the dog back to the vet once the problem has been diagnosed. “Some people do it successfully,” after having been shown the proper procedure by their veterinarian, Dr. Schissler concedes. “But one of the things that’s likely to cause a dog discomfort and anxiety is handling around his anus. If a dog is going to bite you, he’s going to bite you if you’re touching his rear end.” In addition, to do a thorough job of evacuating the sacs, “you need to do it digitally, with a finger in the dog’s rectum, and most clients are not comfortable with that.”

The anal sacs can be expressed externally, by squeezing the anus at the four and eight o’clock positions. In fact, many groomers empty the sacs this way as a routine part of a grooming visit. But Dr. Schissler stresses that this will not empty the sacs entirely. And some experts argue that manipulating the sacs may cause damage and create the very problem that you’re trying to avoid in the first place.

If your dog is having ongoing anal-sac problems and you want or need to learn to empty them yourself, have your veterinarian show you how to do it. Make sure your dog is restrained properly, and be sure that other problems, such as a tumor, polyp, or abscess, have been ruled out. “If the anal sac starts to abscess and you squeeze internally, you’ll make it worse,” Dr. Schissler cautions.

But, she says, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: “If a dog’s not having a problem, I’d just leave them alone.”

Treatment and Possible Anal Gland Complications

While some studies estimate that as many as 12 percent of dogs have had problems with their anal sacs, there is no clear understanding of the cause. One theory suggests that some dogs have very narrow anal-sac ducts that are more prone to obstruction; inflammation from allergies may also block the ducts. Smaller and toy dogs have a greater likelihood of developing anal-sac problems, as do certain breeds, including Cocker Spaniels, Basset Hounds, and Beagles.

“As a dermatologist, I see a lot of dogs with anal-sac issues,” Dr. Schissler says. “My guess is that there are several different causes, but the reality is that it’s not a glamorous thing to study, so there are few studies about what’s normal.”

Regardless of the cause, ignoring anal-sac problems can lead to unpleasant complications: The accumulated material in the sac eventually will begin to thicken, impacting the sac. If infection results and remains untreated, the anal sac can abscess and rupture, allowing the infection to spread into the tissue around the anus and the back of the thigh.

In such serious cases, the veterinarian might prescribe steroid and antibiotic therapy. But unless signs of infection are definitely present, “treatment with antibiotics is not usually indicated,” Dr. Schissler says. And diagnosing a brewing infection doesn’t just mean the presence of bacteria, as all normal anal-sac excretions contain those organisms; the secretions will also contain many inflammatory cells.

While uncommon, anal-sac adeno-carcinomas can metastasize aggressively, and are also signaled by high levels of calcium in the blood. If physical examination rules out a tumor, and an infection is not suspected, Dr. Schissler says a veterinarian might opt to empty the anal sacs and monitor the situation.

Though studies are few and far between, Dr. Schissler says that allergies are suspected to play a role in anal-sac problems. If an allergic response is suspected, a veterinarian might opt to put the dog on a hypoallergenic diet or one with a novel protein, though Dr. Schissler finds that anal-sac problems don’t always respond to a diet change or allergy therapy.

Some anecdotal evidence suggests that an increase in dietary fiber can help resolve anal-sac problems, the theory being that the firmer stool expresses the glands naturally. (Some owners report that raw diets, whose natural-bone content produces very hard stools, are particularly helpful in this regard.) While Dr. Schissler has found that high-fiber diets do not always help, “they can’t hurt,” she says.

The most drastic treatment for repeated, chronic anal-sac infections is surgery to remove the sacs. Not a minor surgery, anal sacculectomy runs the risk of intraoperative bleeding (because the area is so vascular), post-operative infection, and – the outcome that concerns most owners – fecal incontinence. Dr. Schissler notes that when the surgery is done appropriately, by an experienced, board-certified surgeon, the risk of the latter is low.

And she stresses that surgery is very much a last resort. “I’ve been practicing vet medicine for 10 years, nine of them dermatology related, and I’ve only sent two dogs to surgery,” Dr. Schissler says. “It’s not common, and the vast majority of cases can be managed.”

She says she will consider surgery under one of two circumstances: Repeated infections have created so much suspected scar tissue that there is no longer an opening for the anal sacs to empty, or the anal-sac problem is so severe, and has been so unresponsive to medical treatment over time, that the dog’s quality of life is negatively impacted.

With the constant “scooting” and seemingly endless carpet-cleaning that they bring, anal-sac problems are no fun for anyone. Being diligent about noting symptoms and seeking out early veterinary care can ensure that your dog – not to mention that antique Aubusson – both get the relief they need.

A regular contributor to WDJ, Denise Flaim raises Ridgebacks in Long Island, New York.

so whats the best hypoallergenic dog food

Thank you for this article, you’ve shed some light medically on why dogs tend to scoot sometimes.

Personally, just to add some more insight to the article, I believe prevention is better than cure. Diet is a major contributor to a dog’s fecal movement, so we should begin with the end in mind. Give him a consistent diet of foods that would regulate his bowel movement.

I also wouldn’t recommend regularly expressing the anal sacs as you’ve mentioned in the article as this poses a great risk to damaging the linings of the sacs and only allow it when there’s no other choice.

Here’s more information regarding this matter as posted in this blog article: https://goldenretrieverlove.com/why-is-my-dog-dragging-its-butt/

What about WORMS???