Many dogs are amazing athletes, capable of running faster, jumping higher, and displaying better endurance than most human sports stars. But even when they are not very athletic, dogs are hard on their joints, particularly their stifle joints. The dog’s stifle is analogous to a human knee and is commonly (and interchangeably) called a knee or a stifle.

One of the most common athletic injuries in humans is damage to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in the knee. If they haven’t torn it themselves, most people know someone who has. In human athletes, this is known as the “plant and twist” injury. It’s seen most frequently when the foot is planted firmly and the knee is then either twisted or run into (picture those cringe-worthy clips of soccer and football players being hit from the side).

In dogs, we see this same injury, often resulting from the same sort of forces, but we also see chronic wear and tear leading to cruciate ligament tears. To fully understand why this is so, you need to appreciate the mechanics that lead to cruciate ligament injuries.

Canine Knee Anatomy

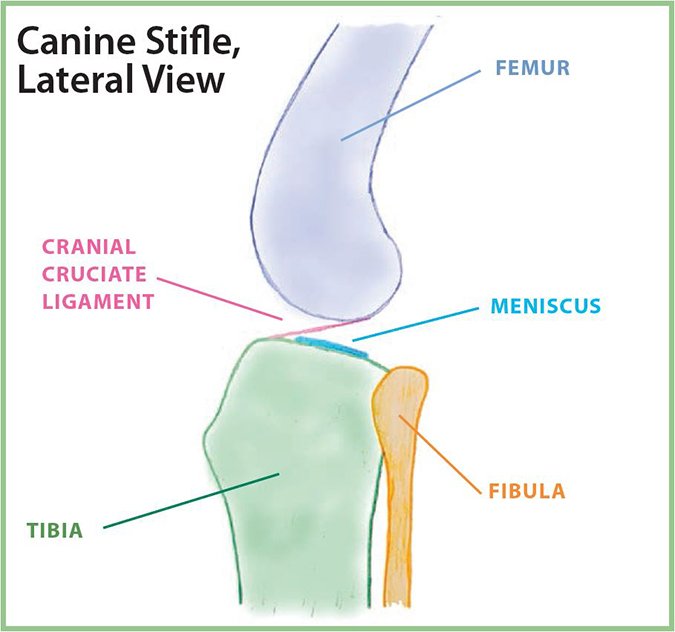

The knee joint in a dog is the point where the thigh bone (femur) and “calf bones” (tibia and fibula) come together and interact. Refer to Figure 1 (right) so you can fully understand what the dog’s knee is up against, literally and figuratively! Here are the anatomical terms you’ll need to know:

Femur – Upper leg bone extending from the hip to the knee.

Tibia – Primary lower leg bone extending from knee to ankle.

Fibula – Secondary lower leg bone extending from knee to ankle.

Stifle – Knee joint.

Cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) – This ligament provides front-to-back stability (and a tiny bit of rotational stability) between the femur and tibia in the knee joint.

Meniscus – C-shaped cartilage cushion that provides shock absorption in a joint.

Dog Knees vs. Human Knees

Picture your dog standing: His knee joints are slightly bent, ready to propel him forward like a coiled spring. Now picture yourself standing next to your dog: Your knees are straight, possibly even locked in place. The disparity in the posture of our knees when we are standing is one of the biggest differences between dogs and humans – and it contributes to the frequency of injuries to dogs’ knees.

The bottom of the femur is rounded in both dogs and humans. The top of the tibia is flat. When a human is standing, that round femur rests neutrally on a flat surface. It takes very little effort to keep that position – and gravity helps. A round structure on a flat surface will pretty much stay in place, as long as that flat surface is level.

Now, think back to the dog. His knee is bent. That means that the round end of the femur is on a tilted platform. Something needs to keep that femur in place.

That something is, in large part, the cranial cruciate ligament. As the name implies, the cruciate ligaments – both caudal (toward the tail) and cranial (toward the head) – form an “X” in the knee joint, holding the femur to the tibia. The cranial cruciate ligament starts at the back of the femur and attaches to the front of the tibia. It is constantly being strained by the natural position that the dog stands in. The slope to the top of the tibia, combined with the round end of the femur, means that the femur is always trying to fall off the back of the tibia.

Ligament Tears in Dogs More Common Than in People

A loose string can be moved around with little risk of breakage, but the more you increase the tension on the string, the easier it will tear. The same is true of a ligament. So, in dogs, with this ligament under constant strain, tears are more common than in the human knee. In fact, this is the most common orthopedic injury that veterinarians see. In humans, this ligament gets periodic “rest” breaks and is really under strain only during physical activity. In dogs, it is in constant use – and over time, especially in large-breed or overweight dogs, it wears out.

A CrCL injury in a young, healthy dog is typically an athletic injury. In older dogs, it is usually an injury of chronic wear and tear. This explains why it’s so common for a dog who has damaged the CrCL on one side to then tear it on the other side. When you take one back leg out of commission, the work load shifts to the other, increasing the strain on the ligaments of the “good” leg.

This is simplifying things a bit. There are many contributing factors to this type of injury, from the dog’s build (conformation) to his activity level. Some things that can predispose a dog to this type of injury include obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, and other joint problems (such as “trick” knee caps). Overweight dogs experience far more strain on their joints than their fit counterparts. Dogs who are not very active also strain their ligaments more, as their untoned muscles don’t contribute much to the task of holding things in place.

Dogs Don’t Have ACLs (They Have CrCLs)

The ligament that provides front-to-back stability in the knee is called the cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) in the dog, but the same ligament in the human knee is called the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Why the different anatomical names?

It has to do with how the front of a quadriped (four-legged animal) is described as compared to the front of a biped (two-legged animal).

In a quadriped, the “cranial” refers to the head end of the animal. The cranial side of the dog’s knee is the side closest to his head.

In an upright biped like a human, the same surface of the knee (as just one example) can’t accurately be described as being closest to his head. Instead, the “front” is called the anterior or ventral surface.

This can be confusing, especially when people refer to a dog’s ACL. It’s not the correct term, but when it’s used, it is meant to indicate the CrCL.

To add to the confusion, the cranial cruciate ligament is sometimes abbreviated as CCL and sometimes as CrCL. Since CCL could also stand for caudal cruciate ligament, we prefer the more precise abbreviation of CrCL.

Dogs Most At Risk for Torn Cruciates

Let’s look a bit deeper at the patients who most commonly present with this injury: small dogs, young big dogs, and old big dogs.

When a small-breed dog, young or old, is diagnosed with a torn cruciate ligament, it’s very important to check for a specific, concurrent problem – medially luxating patellas. This is a fancy way of saying knee caps that slip to the inside of the joint. This is a very common congenital problem for dogs under 20 lbs. When they are born with knee caps that move incorrectly, they are at higher risk for ligament tears because of the abnormal forces on the joint. This is important because it can and should be fixed at the same time as a torn cruciate ligament.

When a young large-breed dog is diagnosed with a torn cruciate, I look for conformation problems. Do his legs bow like a cowboy? Do his paws turn out like a duck? I also ask about activity level, since these are the dogs who will most commonly get this injury through athletic injury, just as with humans.

If it’s an older, bigger dog, it’s usually a wear-and-tear injury, which increases the risk for a tear in the other back leg.

All of these dogs have one thing in common, though: Their risk of a ligament tear is lower if they are fit and at an appropriate weight! Overweight dogs are at a much higher risk for joint problems in general, from arthritis and strains to fractures, dislocations, and ligament tears. Keeping your dog (young or old), active and at a healthy weight will stave off many potential problems.

Diagnosis of Canine Cruciate Ligament Injuries

So now we know the anatomy and the “why” of this injury. Let’s talk about how it’s diagnosed. Any dog who comes in with a back leg limp should be checked for a torn cranial cruciate ligament.

The first clue is a knee joint that feels swollen. Anytime the knee joint is swollen I am on high alert for a ligament tear.

To look for this injury, veterinarians do something called a “drawer test,” which involves moving the tibia in relation to the femur. If I can move the lower leg bone forward in the knee, the cranial cruciate ligament is not doing its job. Sometimes, in a big, strong dog, this requires sedation. But in small dogs, it’s pretty easy to do during a routine physical exam.

Once this injury is suspected, x-rays are the next test. Now, let me say this and say it loud: YOU CANNOT SEE A LIGAMENT ON AN X-RAY. Nevertheless, x-rays are still very important, because they let us double-check for other injuries (such as small bone fragments) and help us evaluate whether arthritis might already exist.

The position of the leg bones (as seen in the x-rays) will also give us clues as to whether and how severely torn the cruciate ligament might be; certain changes in the position of the bones can indicate that the ligaments are not stabilizing the joint properly. Finally, x-rays also help with planning for how to treat the injury (which we’ll talk about in the next issue).

Complicating Factor

A torn meniscus is one concurrent injury that can be suspected, but not diagnosed, until surgery. This is another injury that’s common to both human and canine knees.

The meniscus is a little piece of cartilage that provides cushioning and shock absorption in the knee. When the cruciate ligament is torn, that cartilage starts getting squished and rubbed in an abnormal way, which can lead to tears in the meniscus. A chronically torn meniscus may lead to further arthritis and discomfort in the future. There is no good data on whether or not removing a torn meniscus improves long-term pain control in the joint. Some surgeons recommend removal and some do not, but that’s a discussion to have on a dog-by-dog basis with your doctor.

Future Options

The stifle is a complex joint with a lot of working parts. The joint is prone to injury because of the way it’s formed and the way it’s used in the dog. A cranial cruciate ligament tear is not an emergency, but it’s worth a trip to your veterinarian to talk about options.

Cranial cruciate disease is a constellation of signs and symptoms that have a lot of different management options. We’ll dig into those options in the next issue. Until then, keep an eye on your dog. I bet you’ll notice a lot more of the dynamics of his knees than you did before!

A 2011 graduate of Michigan State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, Kyle Grusling, DVM, practiced emergency medicine for three years before switching to a general practice. Dr. Grusling works at Northland Animal Hospital in Rockford, Michigan.

It’s very helpful information. I have an 11 year old german shepard mix. First, about 8 or maybe even 9 months ago she hurt her right Ccl, that’s what the vet was thinking. All along for at least 4 or 5 years she has had a joint supplement. Things seemed to heal up, but she wasn’t jumping on the bed anymore and then she stopped jumping on the coach. Covid restrictions were put into place and the option of an elective surgery wasn’t an option. I was also worried that I could not lift her as needed after surgery until she fully recuperated. My husband remains opposed to any expense over $200. for any pet, plus there are signs of early dementia in him which could complicate decisions made for the pet in my absence. In the last two months she, our dog tore the ligament in the other hind leg. She was running after a squirrel and all of a sudden yelped, then limped. If everything could be guarantied, of course that would be great, but she is such a lively girl and would chase a wild animal in a heart beat or get up and bark at something outside the window.

I’m thinking the braces would be best because I don’t think she can be restricted for the appropriate amount of time to heal after surgery.

What did you end up doing? I’m having the same decisions to make for my 11 year old Lab.