[Updated August 16, 2018]

Deworming agents are present in any number of prescription and over-the-counter treatments for dogs and puppies. If your dog shows signs of a gastrointestinal worm infestation, there are all sorts of products available that are made exclusively to rid dogs of various types of worms. But there are also deworming agents included – whether they are needed or not – in many flea and tick treatments and in most heartworm preventive drugs; in fact, it’s sometimes hard to find a minimalist flea treatment or heartworm preventive drug that does not contain dewormers. The question is, is this really necessary? Are intestinal parasites that much of an ongoing threat to most dogs – and their owners?

Yes, many of the worms that can infect dogs are zoonotic – that is, they can infect humans, too. (See “Which Worms Can Infect You or Your Human Family?” on page 10.) Now that we have your full attention, let’s start with a description of the most common gastrointestinal parasites that can infect dogs.

Roundworms

Ascarids, more commonly known as roundworms, are the most frequently detected parasite in dogs. The most common species is Toxocara canis, probably because it has the most strategies for infecting dogs of any of the internal parasites, and because the females are such prolific egg-layers (a single worm can lay 100,000 to 200,000 eggs in a day). Toxascaris leonina, another ascarid species, is found less commonly.

Typically, roundworms live in the small intestine, though their larvae may migrate and “encyst” – become walled off and inactive, sometimes for months or even years! Adult worms are usually 3 to 4 inches long, although some T. canis roundworms can be up to 7 inches. Seen in cross-section, they are indeed round and resemble thin spaghetti noodles. Occasionally, adult worms will be expelled in the feces (and more rarely in vomit), but it’s generally the eggs and larvae that are expelled and pose an infection threat to other canine hosts.

Roundworm eggs can exist in soil for years, making them a persistent threat. The parasite is found in every part of North America.

Roundworms can steal much of the beneficial content of what you feed to your dog, absorbing nutrients in the dog’s small intestine and interfering with digestion. Dogs who host only a couple of roundworms may display no symptoms at all, but dogs (and especially puppies) who are more heavily infested may be thin, with prominent shoulder, spinal, and hip bones framing their found, swollen bellies. Their coats are usually quite dull and their energy levels are low and lethargic. They may suffer from diarrhea or constipation, gas, and/or vomiting. Very severe infestations can actually block the intestines and cause the death of their host.

Almost all of the anthelmintic (worm-killing) agents that treat roundworms are effective against only the adult worms living in the dog’s digestive tract; encysted or migrating larvae won’t be harmed by deworming preparations. This makes a good case for occasional treatment with an appropriate deworming agent.

Hookworms

There are actually three species of this nasty parasite commonly infecting dogs in North America: Ancylostoma caninum (canine hookworm), Ancylostoma braziliense (canine and feline hookworm), and Uncinaria stenocephala (Northern canine hookworm). They have notably different geographical concentrations, however; A. braziliense is found in the southeastern part of the U.S. in twice the prevalence it is found elsewhere, and U. stenocephala is found more commonly in northern climates.

Despite their small size (adults are just 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch long), hookworms are highly destructive parasites. Their name comes from a description of the mouth-parts they use to attach themselves to the wall of the dog’s small intestine and feed on his blood. Their aggressive feeding habits can cause obvious evidence of disease in a fairly short time, including anemia and serious diarrhea.

Hookworms produce an anti-coagulant that prevents their feeding sites from clotting and healing, so their hosts lose more and more blood as the infection progresses. The chronic bleeding causes the severely infested dog to produce black, tarry stools and grow weak. His coat will become rough. Puppies’ growth will be stunted. Without treatment, dogs with heavy infestations may become emaciated and die.

Hookworm eggs are expelled in the dog’s feces, and develop into infectious larvae in two to 10 days. Hookworm larvae are extremely aggressive survivors; they can travel in any moist environment (rain-wet or dewy vegetation) and swim in water.

This parasite also uses a variety of methods for entering its host. Dogs can become infected by ingesting larvae-contaminated food, water, vegetation, insects (including cockroaches!) or rodents; or by coming into skin contact with larvae (the larvae can burrow through the skin and migrate through the dog’s tissues). Puppies can become infected in utero (as larvae migrate through the mother’s tissues into the developing fetuses) or through an infected mother’s milk. Larvae that migrate through the dog’s body sometimes become encysted in muscles, fat, or other tissues and this can cause pain and discomfort.

Hookworms pose a special diagnostic problem; infections are generally detected via examination of a fecal sample from the dog for the presence of worm eggs. But hookworms can cause serious disease in puppies before the worms are old enough to produce any eggs. A diagnosis of hookworm infestation may have to be made from the observation of disease, rather than a fecal examination.

Whipworms

Canine whipworms (Trichuris vulpis) are found all over the world, and though their infections are much less likely to cause observable symptoms of ill health in a dog, a really severe infestation can cause bloody diarrhea and weight loss. They are not nearly as prolific reproducers as roundworms, with the adult females producing a much smaller number of eggs and much more intermittently. However, these eggs are extremely resistant to dessication (being dried out), extremes in temperature, and ultraviolet radiation; they can remain viable in soil for years.

Dogs are infected by eating whipworm eggs that are present in feces or in soil, or on plants that came in contact with contaminated feces. Larvae hatch from eggs in the small intestine and move into the cecum (the first part of the dog’s large intestine) as they mature into adult worms. The adults are rarely expelled into the dog’s stool, so the worms are seldom seen, making it more difficult to diagnose a whipworm infestation.

Adult whipworms are much smaller than roundworms, only about 11/2 to 3 inches long. The “head” end of the worm is threadlike and thin and the tail end is thicker; so the sum effect is that of a long-lashed whip with a sturdy handle.

The adults consume blood, tissue fluids, and tissue from the cecum’s mucosal epithelium; their feeding habits can trigger inflammation in the cecum, resulting in the overproduction of intestinal mucus, which can be observed in the feces of their host.

Tapeworms

There are two major types and at least 10 species of tapeworms that infect dogs in North America – so many that we won’t bore you with all the names of them. They are considered ubiquitous wherever there are flea-infested dogs, but their prevalence isn’t calculated like the other intestinal parasites, because they can’t be reliably detected (and their incidence quantified) through fecal examination or fecal floatation tests.

Adult tapeworms live in the dog’s small intestine, where they hook onto the walls of the intestine. Unlike hookworms, however, they do not feed on the dog’s blood; they absorb nutrients through their skins (robbing the dog of nutrients in its diet) like roundworms. They can be 6 inches or longer, but few ever see them in this long form, because they grow in “segments” that emerge from the worm’s “neck” area, with older and older segments being pushed toward the worm’s tail. Each segment is about the size of a grain of rice and contains a complete set of organs, but as the segments mature, all but the reproductive organs deteriorate. These older segments at the end of the worm eventually transform into a sac of eggs and then separate from the body of the worm; they then are expelled from the dog in its feces.

While these worms cause the least harm to the dog of any of the parasites mentioned here, they often alarm dog owners the most, due to one simple fact: most owners will be able to see (and be horrified by) tapeworm segments that have emerged from their infested dog. The segments often stick to the hair and skin around the dog’s anus, and upon close examination, can be observed to be moving! Many a startled owner has called her veterinarian to report that her dog has “maggots” on its bottom, only to learn these are tapeworm segments.

Tapeworms can infect the dog in one (weird) way only: they require an intermediate host. Fleas are the usual intermediary, but lice can be, too. Larval fleas (or larval lice) consume the eggs that emerge from tapeworm segments (remember that they are nothing but egg sacs by the time they are expelled from the dog), and the eggs start to develop into tapeworm larvae inside the developing flea or louse.

The tapeworm larvae uses the flea like a Trojan horse; it gets into the dog inside a flea! Dogs accidentally (or incidentally) consume fleas when they groom themselves (or chew themselves to relieve an itchy flea bite). Long story short: your dog can’t become infected with tapeworms unless he’s exposed to infected fleas.

Tapeworm eggs don’t often show up on a fecal flotation test, even if a dog is heavily infested with adult tapeworms, because the eggs generally stay contained in the segments until those egg sacs break open, which may take days after the segments passed out of the dog and his feces. But the presence of a tapeworm segment on or around a dog’s anus is a clear sign that he needs anthelmintic treatment.

Taking Action

Now that you know the players, how do you stop the game?

Thirty years ago, the prevalence of these intestinal parasites was two to three times what it is today. In decades past, dogs were routinely dewormed only as puppies, or if they developed obvious signs of an infestation and their owners sought veterinary attention. Today, with anthelmintic agents included in so many products that are administered for control of other parasites (such as flea, tick, and heartworm preventives), the overall incidence of intestinal worms is much lower in the overall population of North American dogs.

That said, many dogs originate from or are raised in circumstances where little veterinary care is given. Dogs who are rescued or purchased from crowded and/or neglectful homes, shelters, hoarders, or puppy mills will almost certainly be infested with every known variety of intestinal parasite. Puppies who were born to dogs from those circumstances will also be infested and require several treatments to be rid of worms.

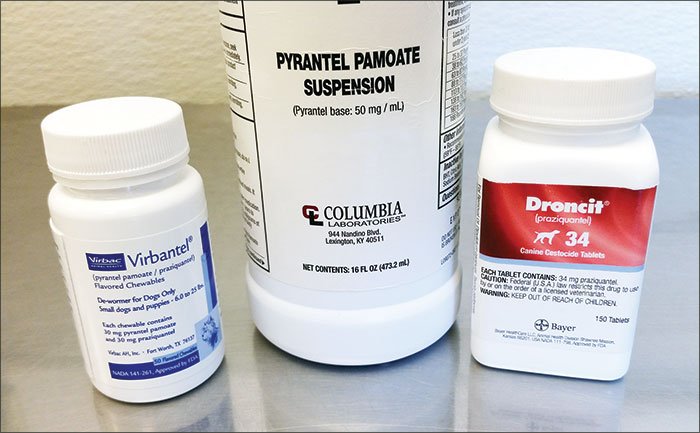

There are a lots of anthelmintic products available to dogs owners; there are products that you can buy over the counter, and drugs that require a veterinary prescription. There are products that are targeted to treat intestinal worms only, and combination products that also control external parasites and/or prevent heartworm. (For more information about heartworm prevention, see “Sick at Heart,” WDJ July 2011.)

What kind of treatment you use should depend on your dog’s age and health. Treatment will need to be repeated at certain intervals, depending on the parasite. Most anthelmintics affect only the adult stage of worms; repeated doses (usually in about three weeks, and again in two to three months) will be needed to eliminate any worms that were present in the dog in larval stages and unaffected by earlier treatments.

If specific intestinal parasites have been identified in your dog, it’s wise to use agents that are specifically indicated for those worms, rather than relying on broad-spectrum treatments.

As just a few examples, milbemycin oxime and moxidectin are included in a number of heartworm preventive drugs, and are also credited with effectiveness against roundworms, hookworms, and whipworms; pyrantel pamoate (the “plus” in Heartgard Plus) is effective against roundworms and hookworms only. But we’ve heard of dogs who have routinely received these heartworm preventive drugs and still were diagnosed with severe intestinal parasite infections.

There’s also the issue of the dog getting reinfected, especially if your dog eats feces, frequents areas where the soil has been heavily contaminated (such as dog parks), and/or if your yard was previously contaminated by neglected dogs. Environmental decontamination can be difficult, and the eggs of some of these parasites can persist for months or even years in the ground. Regular fecal exams (and treatment) for dogs in these situations are recommended.

Natural Deworming Remedies?

People who strictly adhere to “natural” dog-raising practices often eschew veterinary deworming agents in favor of traditional remedies such as wormwood (artemisia), black walnut hulls, ground pumpkin seeds, food-grade diatomaceous earth, and others. In the view of many experienced holistic veterinary practitioners, however, some of these remedies turn out to be more toxic – more dangerous to dogs! – than conventional veterinary treatments. They may be ineffective as well, especially if non-toxic doses are used.

And while it’s true that a healthy dog, fed a superior diet and living in a clean, healthy environment, should have the benefit of a robust immune system response to help combat parasitic invaders, parasites, too, are capable of being quite robust. In our opinion (and that of many holistic practitioners) counting on the unverifiable “strength” of your dog’s immune system to prevent intestinal parasites is asking for trouble.

The natural approach may seem to prevent worm infestations in healthy, well-cared-for adult dogs who were produced by well-cared-for mothers, but the truth is, the incidence of worms in that lucky (and minority) population is bound to be low no matter what. Treatment of existing infections and prevention of reinfections in vulnerable dogs and puppies should be undertaken by more reliable, conventional anthelmintic agents.

“Fecal Float” Tests

Most intestinal parasite infestations are diagnosed by examining a fecal sample from the dog. Sometimes, adult worms (or in the case of tapeworms, worm segments) can be readily identified in the poop itself. More frequently, however, veterinarians perform what is called a “fecal flotation” test. The feces is mixed with a solution that causes any worm eggs present in the sample to float to the top; sometimes, the mixture is also spun in a centrifuge, to concentrate any eggs present. A sample of the floating material is then examined under a microscope.

If any eggs of any intestinal parasites are present in the sample, they are readily identifiable in a microscopic view. However, a dog may be heavily infested with worms that are not yet old enough to produce eggs (this is especially true in young puppies), or the sample may have been taken on a day when the worms did not produce eggs. Some worms produce only small numbers of eggs and only infrequently. For these reasons, many veterinarians recommend periodic “fecal float” tests – more frequently when a dog is young, and especially if the dog shows signs of a heavy worm burden upon physical exam (including a thin, pot-bellied body condition; poor coat; or persistent lethargy).

Which Parasites Can Infect Humans?

Roundworms: Humans can become infected by unwittingly ingesting infective eggs. Roundworm eggs can build up in the soil where infected dogs eliminate. Infection can result if you get these microscopic eggs on your hands (say, by getting dirt on your hands in the process of doing yard work), and then eating something with your hands.

If you become infected with roundworm larvae, you can develop a condition called “visceral larva migrans” – severe inflammation caused by the migration of the larvae through your tissues. Signs of this disease include an enlarged liver, intermittent fever, loss of weight and appetite, and a persistent cough. Asthma or pneumonia may also develop. “Ocular larva migrans” is a condition caused by roundworm larvae migrating through a human’s eye, causing partial or complete loss of vision.

Hookworms: Humans can much more easily become infected with hookworms than roundworms, due to the hookworm larvae’s ability to migrate through skin (such as bare feet or hands) into tissues. As with roundworms, the migration of hookworm larvae through human tissue can cause a serious inflammatory condition known as cutaneous larva migrans.

Tapeworms: Humans can become infected by tapeworms, but it takes some doing; just as with dogs, a human has to ingest a flea that is infected with tapeworm larvae in order to become infected himself.

Preventing these infections is relatively simple:

Periodically treat your dog for intestinal parasites. If your dog eats dog and/or cat poop, treat him for parasites regularly.

Pick up dog feces in your yard frequently. It would be ideal if you could pick up and dispose of your dog’s poop immediately after he eliminated; this would minimize the chances of any worm eggs or larvae lurking in your yard.

Wash your hands. A lot! And especially after being in any environment where lots of strange dogs have eliminated. And before eating, any time you’ve been around soil where dogs have been. Don’t ever eat food with your unwashed hands in a dog park, for example.

Avoid bare skin contact with ground where dogs eliminate. We’ve been to plenty of dog parks and off-leash areas and witnessed people (worse, small children) walking barefoot – yikes! Remember, hookworm larvae need only skin contact in order to migrate into your body.

Protect your dog from fleas. And treat him for tapeworms (and fleas) immediately if you see tapeworm segments on him or in his feces.

Will apple cider vinegar kill worms in puppies

“@ Melissa,

Really? Apple cider? How sure you are that it’s safe for canine? I mean, do you have something to share here with us? So we could know when and how to apply for them the exact ratio and dosage. A sort of interesting to me. I have this apple cider in my house, and I use this for some home remedies. Perhaps I could use this too to my canines. For further reading, I guess this one might help too https://ultimatepetnutrition.com/worms-dog-poop/“

Apple cider VINEGAR. Not just apple cider. There is a difference.