For people living with disabilities, a dog can be the key that opens the door to independent living. It’s been estimated that there are more than 500,000 service-dog/handler teams in the United States, and by law, these teams are accorded the right of access to nearly every place that the human handlers can go. Most dog owners love seeing well-trained service dogs enabling their disabled humans to ride public transportation, navigate shopping and workplaces, and enjoy a night out in restaurants and the theater.

Few of us, however, like seeing obviously untrained or out-of-control dogs in public places where they may reflect badly on the service-dog industry. They may also engender hostility from business owners and managers, who often feel they have no recourse when ill-mannered dogs wreak havoc in their establishments.

We discussed the moral and legal considerations associated with the growing problem of “fake service dogs” in “Artificial Needs” (WDJ July 2013). It’s a complex conundrum, in part due to the Department of Justice’s use of an “honor system” as to whether or not a dog is a trained service animal, the various agencies involved, and the challenging nature of drafting regulations designed to protect – without infringing upon – the rights of those living with a disability.

Adding to the confusion is another class of companion animals who, teamed with their disabled handlers, are accorded expanded rights of access in certain situations: emotional-support animals, often referred to as “ESAs.” Many people believe – falsely – that emotional-support animals are allowed to go anywhere with their handlers that service-dog/handler teams can go.

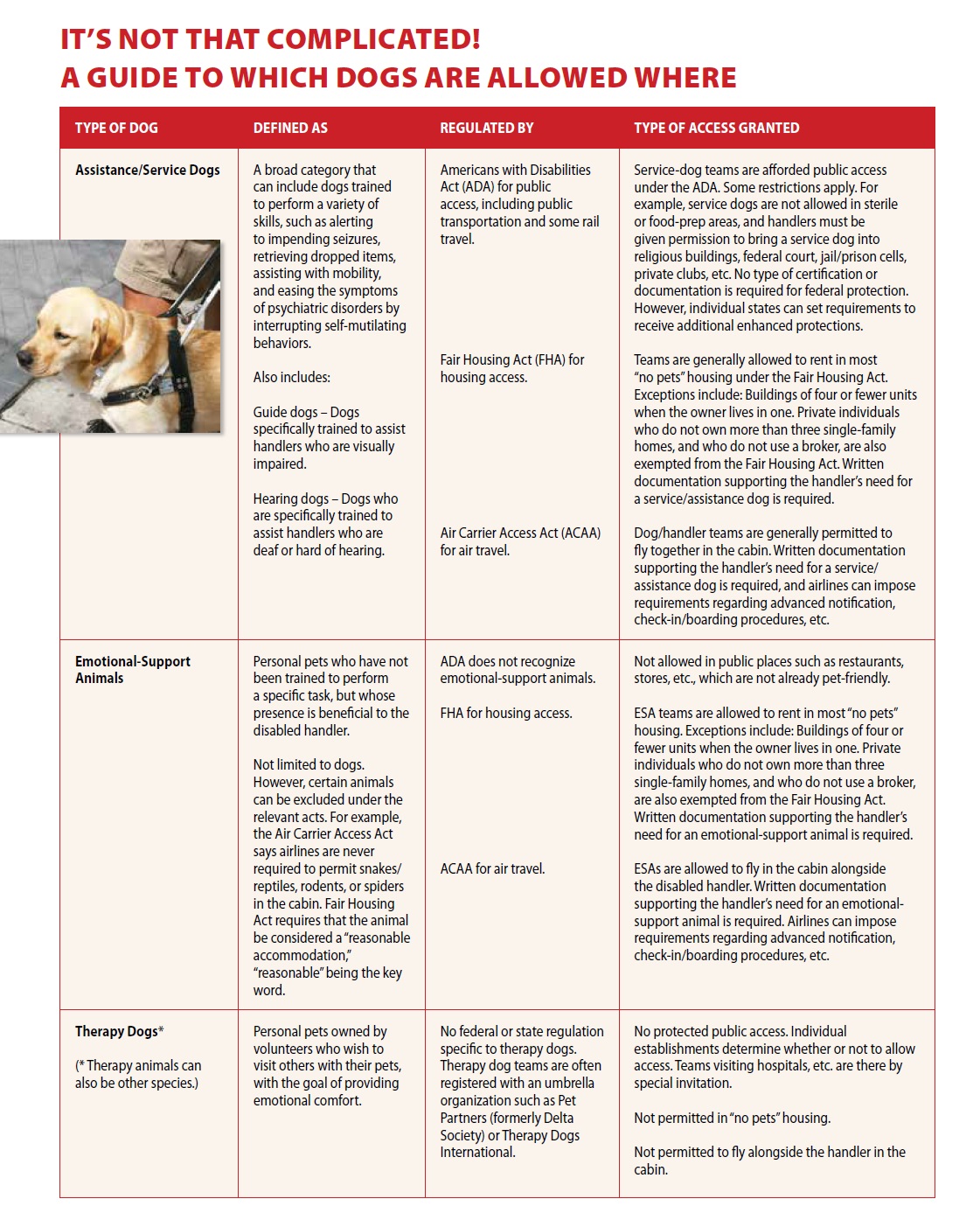

It seems that almost everyone is confused about which dogs can go where, and how one can determine which dogs are legitimate helpers and which are pets whose owners may be taking advantage of the confusion! Let’s sort it all out.

(If you’re just looking for a quick breakdown of the different types of assistance dogs, check out this article from Dogster.com.)

The Americans with Disabilities Act

The law that gives service-dog/handler teams the right to enter places where dogs are not usually permitted is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). First enacted in 1990, the ADA is overseen by the United States Department of Justice. An amendment process began in 2008, with revisions to the Act taking effect in 2011. (Technically, the current regulation is known as the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendment Act (ADAAA), though most people still refer to the “ADA” when referencing federal service-dog law.)

The ADA was enacted to “provide a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities,” and to protect a disabled person’s access and right to “fully participate in all aspects of society.”

The ADA defines a disabled person as one who “has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment.”

The phrase “major life activities” is defined in the ADA as including “caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, standing, lifting, bending, speaking, breathing, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, communicating, and working.”

The ADA recognizes that disabled persons may require “reasonable accommodations or auxiliary aids or services” in order to “fully participate in society.” Service animals are included as one of those aids; that’s why dog/handler teams are granted expanded rights of access to areas that are typically off limits to animals. Under the ADA, “state and local governments, businesses, and nonprofit organizations that serve the public generally must allow service animals to accompany people with disabilities in all areas of the facility where the public is normally allowed to go.”

Currently, only dogs and miniature horses who have been individually trained to do work or perform tasks for a disabled person may be considered service animals. (Miniature horses are regulated with slightly different guidelines; we will discuss only service dogs in this article.)

Keep in mind that it’s the task that the dog is specifically trained to perform, in order to entirely or partly mitigate the handler’s disability, that gives handlers the right to have that dog in public areas that are typically off limits to dogs. The ADAAA’s definition of a service animal includes these clarifications:

“Examples of such work or tasks include guiding people who are blind, alerting people who are deaf, pulling a wheelchair, alerting and protecting a person who is having a seizure, reminding a person with mental illness to take prescribed medications, calming a person with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during an anxiety attack, or performing other duties. Service animals are working animals, not pets. The work or task a dog has been trained to provide must be directly related to the person’s disability.”

The ADA imposes reasonable restrictions on the use of service animals in public; the Act is certainly not a license to bring just any dog anywhere at any time. The dog must be harnessed, leashed, or tethered, unless the device interferes with the animal’s ability to work, in which case the individual must still be able to control the animal through voice commands, hand signals, or other means of effective control.

The dog must also be well-behaved and entirely under control. “Through the ADA, if a dog is misbehaving in public – if they’re in a restaurant and the animal is not house-trained, or is eating food off of the table, the business owner has the right to ask the individual to remove the dog from the premises,” says Jeanine Konopelski, a spokesperson for Assistance Dogs International (ADI).

The ADA also states that, in some cases, it might be appropriate to exclude a service animal. For example, although a service dog can’t be excluded from the general-access areas of a hospital (patient rooms, exam rooms, or the cafeteria), he can be reasonably excluded from operating rooms and other sterile environments.

Protecting the Rights of the Disabled

Of course, ordinary dogs are barred by law from many public areas. But disabled people can bring their trained service dogs with them almost anywhere, because the ADA makes it against the law to discriminate against or restrict access to disabled persons – in this case, ones who are using an auxiliary aid (a dog) to mitigate their disabilities. When a business owner or employee is unsure whether the dog is a service animal, he may ask only two specific questions of the handler:

1. Is the service animal required because of a disability?

2. What work or task has the animal been trained to perform?

Staff may not inquire as to the specifics of the handler’s disability, require any special documentation, or ask that the animal demonstrate its ability to perform the work or task. However, the handler’s answers must be credible. “He’s trained to dance on his hind legs and it makes me happy,” would not qualify as a credible answer to Question 2. The trained tasks must be relevant to the handler’s disability.

Emotional Support Animals

Now, buckle up, because this is where the ride gets bumpy.

There is another type of commonly referenced animal that assists disabled humans and is granted greater access in certain situations than most pets: the “emotional-support animal” (ESA). These are personal pets (different types of animals, not just dogs, can be used) who have not been trained to perform specific tasks, but whose presence is physically or psychologically beneficial to their disabled handlers.

It’s a safe bet that many of us would be happier if our dogs were allowed to accompany us on all of life’s adventures. But there’s a significant difference between being happier when in the company of a beloved pet dog and experiencing a psychiatric disability in its absence. The key word is disability, which must meet a clearly defined standard. In order to qualify as disabled, one or more of a person’s activities of daily life must be severely impacted by the condition. A treating medical provider must diagnose the individual’s disability and state that having access to the animal will benefit the disabled handler.

A team comprised of a disabled person and her emotional-support animal does not qualify for any special protections by the ADA, which states clearly, “Dogs whose sole function is to provide comfort or emotional support do not qualify as service animals under the ADA.”

However, there are two other federal departments that grant ESA/handler teams more access than people with ordinary pets. Their access to housing that is otherwise not available to people with pets is protected by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s “Fair Housing Act,” and their access to air transportation is protected by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s “Air Carrier Access Act.”

Both Acts stipulate that the disabled person has a letter from his or her treating medical professional corroborating the disability, and the professional’s opinion that a specific emotional-support animal ameliorates the symptoms of disability.

The Fair Housing Act prevents landlords from refusing to make reasonable accommodations in rules and policies (such as a “no pets” policy), as needed in order for a disabled person to use the housing. Service dogs and most emotional-support animals are considered reasonable accommodations. There are some exceptions to this provision of the Fair Housing Act; for example, a person with an ESA may be denied housing in a building containing four or fewer units where the owner lives in one, and in cases where an individual who owns three or fewer single-family homes and does not use a broker to manage those homes.

The Air Carrier Access Act states “carriers shall permit dogs and other service animals used by persons with a disability to accompany the persons on a flight.” Airlines are not required to permit emotional-support snakes (or other reptiles), rodents, or spiders in the cabin.

People often ask about the difference between PTSD dogs (that is, dogs who are used to assist a person who has been diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder) and emotional-support dogs. PTSD dogs are a type of psychiatric service dog. Like all legitimate service dogs, PTSD dogs have been trained to perform specific tasks that mitigate the handler’s psychiatric disability. For example, a PTSD dog might be trained to recognize and respond to an impending panic attack or interrupt self-mutilation behaviors.

Emotional-support dogs are not trained to perform specific tasks related to the psychiatric disability, yet in many cases, the dog’s presence is considered physically or psychologically beneficial to the disabled handler.

To review: PTSD dogs are service dogs and emotional-support animals are not. Handlers with medically necessary emotional-support animals can fly with their animal and request that the animal be accepted in most housing situations that wouldn’t otherwise allow pets. However, they are not allowed in typical “no pets” areas such as inside restaurants, shops, hospitals, office buildings, etc.

Service Dog FAQs

When it comes to navigating the seemingly endless sea of information pertaining to service-dog law, the following questions are most commonly asked:

Do all service dogs come from professional organizations?

No. Service dogs are not required to be trained by a professional organization in order to earn the ADA’s right to access, and many handlers choose to self-train their dogs. However, it’s important that prospective handlers carefully evaluate their own skills when deciding whether to self-train, train with the help of a professional trainer, or look for an already trained dog from a reputable organization.

For a person who has never previously had a dog, working with a service-dog program can be helpful. Dailyah Rudek, a service-dog law and mediation expert and executive director of The ProBoneO Program, says, “For someone who is a novice dog handler, we definitely have a bias toward a program-trained dog.”

Handlers with a bit of dog training experience under their belt have access to myriad resources to assist them throughout the owner-training journey. Rudek says it’s imperative that those looking to owner-train familiarize themselves with – and utilize – as many of the resources as possible.

“If folks are diligent about it and go step by step, and if they’re lucky enough to get a dog who has the right temperament, owner-trained dogs can be incredibly successful,” she says.

People searching for a professionally trained service dog must exercise due diligence. While the members of ADI are screened as part of their paid membership, dog training remains an unregulated industry, which means any trainer can advertise “trained service dogs” for sale, often with shockingly high price tags.

“People need to be beyond careful,” Rudek says. “You hear stories all the time – people who paid $10,000 for a dog and it doesn’t even know how to sit. I wouldn’t pay that kind of money unless I knew they had successfully trained at least 15 different teams, and I’d had a chance to speak with some of those satisfied customers and see them in action.”

Are service dogs required to be certified?

No. There is no legally recognized, nor federally required, national certification for service dogs, nor is there a legitimate national registry for service dogs. However, a quick Internet search reveals any number of websites offering to “register” a dog as a service dog – for a fee, and without any type of evaluation. Such sites typically sound authoritative, with names boasting words such as “national,” “United States,” and “official,” and offer things like registration certificates, photo identification cards, and service-dog patches – all for a price.

While it is not required, some legitimate dog/handler teams choose to pay for the official-looking paperwork and other accessories, as showing such items sometimes simplifies access issues when dealing with business owners who are not familiar with the law. However, to those truly knowledgeable of the regulations, such paraphernalia is a potential red flag.

“Personally, I am inherently suspicious of anyone who shows me an identification card because the law says you don’t need one,” cautions Matthew Karpinski, chief legal officer for The ProBoneO Program.

It’s also been said within the service-dog community that legitimate handlers who choose to show things like identification cards inadvertently make it harder for those within the community who don’t, because it sends a mixed message to businesses, many of which become more resistant to teams who lack the same gear.

Are there any standards for service dogs at all?

The answer to this depends on what is meant by standards. As discussed above, service-dog/handler teams don’t need any official certifications in order to have public access. However, many service-dog advocacy organizations, including International Association of Assistance Dog Partners and Assistance Dogs International, promote a similar set of minimum training standards for service dogs, which they recommend handlers meet or exceed when training or working a service dog in public.

The two above-mentioned organizations address a minimum number of training hours for basic obedience and public access-specific issues. They also provide basic guidelines for obedience and the ability to perform disability-related tasks on cue. The standards state that a service dog must not display any signs of aggression (either natural or elicited on-cue, such as in protection work), and further include the handler’s responsibilities as part of the dog-handler team.

Both sets of standards can be used as a road map of sorts for handlers wishing to train their own service dogs, or when training in partnership with a professional trainer. They are also used by professional organizations that provide fully trained service dogs. When a dog/handler team successfully meets the minimum standards or passes the public access test, the team is often considered “certified” by virtue of meeting the standard. It’s a tricky choice of words, as it likely contributes to the public’s confusion regarding the lack of a legally required certification. (Perhaps referring to such dogs as “verified” versus “certified” would lessen the confusion?)

“We at ADI call a dog who has passed our public access test a ‘certified dog,’ but it’s not a certification that’s required by law,” Jeanine Konopelski explains. “It’s sort of like, if you work in finance and you have an MBA; you’re not legally required to have that certification. The certification is something we do to make sure that the dog can abide by and adhere to the different guidelines for public access,” she adds, pointing out that the certification is for the dog/handler pair as a team and not the individual dog.

Why isn’t there a national certification for service dogs?

Experts cite two major challenges of implementing a national certification process for service dogs: Who would be responsible for testing, and how would such a program be funded?

“The disabled are statistically in the lowest economic bracket,” Rudek says. “To have a test become mandatory, you’d have to make it super accessible to a bunch of people, many of whom don’t drive and who have no money. How do you make that work? Many people say, ‘Well, what about making it like a driver’s license?’ and the problem with that is that driving is a privilege, not a right. If you’re disabled, having your service dog with you is a civil right.”

Currently, a Canadian province is exploring new regulations that will potentially limit access to “no pets” areas to only those teams trained by professional ADI partners and the International Guide Dog Federation. Such a move, while likely initiated in an effort to raise the training standards, could severely limit the disabled community’s access to service dogs. Karpinski estimates that in the United States, only 1 to 5 percent of all service dogs are trained through a professional training organization.

Can states pass different laws to protect or prohibit the use of service dogs or ESAs?

Service-dog law is complicated by the fact that there are two levels of legislation to be considered – state and federal, says Karpinski. While the ADA provides federal protection for the public access of service-dog teams that meet its qualifications, individual counties and states have the option of drafting additional laws that extend ADA accommodations. For example, many states have their own laws that prohibit denying access to a service-dog team, making it a state crime that carries a hefty fine. States may not, however, pass legislation that limits the disabled person’s protections to less than what the ADA provides.

The difference between state versus federal protection is most relevant when addressing public access violations. If a team is denied access where it is against state law to do so, the police can be called and the issue is likely to be promptly resolved. In states without that enhanced protection, the team’s only recourse is to file a complaint with the Department of Justice – a much longer process.

Can states require that service dogs be certified, or require that handlers show proof that the dog has been vaccinated?

Remember, state laws cannot be more restrictive than federal law. Therefore, states can’t require any special certification in order for the team to be granted the public access rights that are outlined in the ADA. However, individual states can designate certain requirements in order for the team to receive state-specific enhanced protections.

For example, let’s say the law in a handler’s state specifies that service dogs must be identified via orange vests. The handler may choose not to follow this rule, since state laws cannot be more restrictive than federal laws, and the ADA does not require service dogs to work in vests. However, should an issue arise – say, a local business owner denies the team access – the handler will not have state law on his side. It’s still a crime to deny the team access, but the denial must be dealt with through the Department of Justice as a federal rights violation as opposed to a state law violation.

Regarding proof of vaccination, Rudek says it’s likely that states assert that service-dog handlers must be ready to show proof of vaccination for rabies by virtue of the numerous jurisdictional laws that say all dogs must have current rabies vaccinations. “In many cases, courts have found that the presence of a current rabies tag on the service dogs’ collar is sufficient proof that the dog is up to date on vaccinations,” she says.

Are service dogs in training protected by the ADA?

No. ADA’s public access protection is extended only to service dogs who have been successfully task-trained to mitigate the handler’s disability.

That said, individual state laws may address service dogs in training. Where they do, the laws are as varied as the states’ topography. For example, in Montana, handlers with service dogs in training are granted public access provided that the dogs are clearly identified as such. Georgia and Virginia specify that dogs in training must be with professional trainers. Michigan also specifies that dogs in training must be with professional trainers, and the state’s Department of Labor even maintains a list of approved trainers. The trainers must show photo ID stating they are representatives of an approved organization, if requested.

We all love dogs, and anytime we bring a dog out in public – anywhere that dog is legally allowed to join us – we have a responsibility to ensure that the dog can behave appropriately. Ill-behaved dogs are seen as a nuisance and can indirectly create additional challenges for people who rely on service dogs. Handlers of service and emotional-support dogs have enough challenges, without having to face discrimination or hostility over the use of their canine aids.

Also With This Article

When Talking About Assistance Dogs, Words Matter (but variations are common)

Taking Advantage of the ADA, Fair Housing, and Air Carrier Access Acts?

When Service Dogs Misbehave: Acknowledging Inappropriate Dog Behavior in Public

Regarding Those Online Prescription Letters for Emotional Support Animals

If people want to make sure every dog has been trained by a professional trainer then the simple solution is to make the $20,000 -$30,000 available for the professionally trained service dogs and not just for veterans or autistic children. While they are deserving of service dogs so are others who have PTSD and physical disabilities and of course when children grow up autism doesn’t magically go away just because they aren’t as cute as they were as children! Even blind people have difficulty getting a service dog to help them be independent. Getting a professionally trained service dog is a lot like winning the lottery and usually just children and veterans are given a golden ticket so until it becomes easier for the needy to have access to a service dog that they don’t have to try to train themselves I think unless a dog is behaving extremely badly then people need to stop trying to be the service dog police! It’s not their job to decide if that golden retriever is a little bit off of a tight heel or something equally trivial! If a dog is behaving viciously then by all means go tell the manager but this obsession with the fake service dog when 95% are being owner trained leads me to believe that there’s a lot more dogs who are in training by a disabled person than fake service dogs breaking the law!