If you are ever in California, you might want to make it a point to visit Carmel Beach, at the end of Ocean Avenue in Carmel Village, Monterey County. Carmel Beach is a canine utopia. Dogs are allowed, even encouraged, to run off-leash along a breathtaking Pacific Ocean backdrop. On any given day, at any given time, you’ll see Golden Retrievers racing along the sand after tennis balls, Labradors fetching sticks from the surf, Border Collies herding shorebirds, and any and all varieties of mixed-breeds and purebreds romping together in happy groups. Rarely, if ever, does a fight happen. Oh, an occasional brief scuffle maybe, as two ball-obsessed Aussies squabble over possession rights. But it’s hardly ever serious.

Thus the community of Carmel was shocked two years ago when a Pitbull terrier attacked and killed a small Poodle. What happened? Why was there bloodshed on the normally peaceful Carmel Beach?

Dogs are pack animals. Their wild ancestors necessarily had to get along for the very important purpose of survival. Even after thousands of generations of domestication, most dogs still play well with others of their species. When they don’t, it’s usually for one or a combination of three reasons: genetics, learned behavior, or poor socialization.

It’s in the genes

Sadly, humans have bred some dogs for dog aggression, most notably the Pitbull. Dogfighters deliberately selected for dogs who were willing and eager to fight with their own kind until, over time and generations, the quality that they call “gameness” was deeply instilled in the gene pool. A litter of puppies from fighting lines must often be separated by the age of seven weeks or they will fight with each other and cause serious harm. Chances are the tragedy on Carmel Beach was a result, at least in large part, of those genetics.

Other types of dogs were bred for the exact opposite quality. Because they hunt in packs, scent hounds such as the Beagle, Bloodhound, and Foxhound were bred to be exceptionally amenable to pack life. (This is one of the reasons Beagles are often the breed of choice for research colonies.) Other breeds fall on a continuum, from the relatively gregarious sporting breeds like Labrador and Golden Retrievers who are generally good with other dogs, to the guard-type dogs like Rottweilers and Chows, who have a greater tendency to be dog aggressive.

Learned behavior

To some extent, the natural tendencies bestowed by a dog’s genetic package can be influenced by learning. Beagles can be made to be dog aggressive under the right (wrong!) circumstances. Some Pitbulls can be raised peacefully with other dogs, providing care is taken to avoid exposing the individuals to incidents that might turn on their fighting “lightbulb.” This is why it is critical to raise your dog in an environment that doesn’t allow him to be teased, tormented, or attacked by other dogs. Tying a dog up or fencing him in a location where other dogs can agitate the confined one, is a classic recipe for dog aggression.

Poor socialization

But by far the most common cause of inadvertently induced dog aggression is lack of proper socialization. While some veterinarians still urge their clients to keep their young puppies cloistered until they have completed their vaccination series at age four to six months, more and more animal care professionals are recognizing the importance of early socialization with other puppies and dogs in a controlled environment.

Playtime with other puppies and non-aggressive adult dogs gives a puppy the opportunity to learn how to talk and read “dog-ese” through appropriate interactions with and responses to other dogs’ body language. If this doesn’t happen during the pup’s critical learning period, well before the age of six months, you may end up with a canine social nerd whose inept use of the dog’s physical and postural language consistently gets him trouble. This happens either because he sends inappropriate messages or fails to respond appropriately to another dog’s message.

As with virtually all dog behavior problems, prevention is a far better approach than rehabilitation. If you have the luxury of working within your puppy’s critical learning window, you are light years ahead of the game. The more your pup’s breed characteristics and individual personality predispose him to dog aggression, the more critical it is that he be socialized during the learning period. The following steps can maximize his opportunities for socialization while minimizing his exposure to disease:

• DO keep him current on his vaccination schedule. (Some people vaccinate their dogs far more aggressively than others. See “Current Thoughts on Shots,” August 1999 and “Reduced Vaccination Schedule,” September 1999. Also, see sidebar below.)

• DO invite friends over with their healthy puppies and gentle adult dogs to play with your puppy.

• DO enroll your puppy as soon as possible in a well-run puppy class where classmates are allowed to play together. Again, people vary in their willingness to vaccinate their dogs. Most trainers require proof of vaccinations for all participants. People who use fewer than the usual number of puppy vaccinations may have difficulty finding a trainer who understands and accepts this approach.

• DO talk to the trainer and watch the class first. Puppy play should be closely monitored to avoid bullying of small or timid puppies by bigger, older ones. The facility should be clean indoors and out, and training techniques involving the use of choke chains, prong collars or physical force should not be permitted.

• DO intervene if another puppy starts to bully yours. A pup can learn to be defensively aggressive if he is frightened by the intensity of another pup’s play.

• DO intervene if your puppy starts to bully another. A gentle interruption of the behavior every time it occurs combined with brief time-outs if necessary, offset by praise and treat rewards when he is playing well with others, can keep him on the right track. A time out is what behaviorists call “negative punishment.” The puppy’s behavior (being too rough or aggressive) makes a good thing (playing with other puppies) go away. If you are consistent he will learn that he has to be nice if he wants to keep playing.

• DON’T intervene if two pups are engaged in mutually agreeable rough play. Rough play is perfectly acceptable if both pups are enjoying it. Do keep an eye on the participants to make sure they are both having fun, and gently intervene if the tone of play starts to change.

• DON’T take your puppy to dog parks or public areas where lots of dogs congregate. He faces a much greater risk of exposure to disease in those environments.

• DON’T allow your puppy to sniff piles of feces from unknown dogs when you take him for walks around the block.

• DON’T allow your pup to interact with any dogs or puppies who don’t appear healthy, and don’t allow the owners of sick dogs or puppies to play with yours.

If you follow these simple guidelines, your chances of having a well socialized dog are high, and your disease risk is very low. Remember: Far more dogs face tragic ends to their lives due to poor socialization than to illnesses encountered in well-monitored puppy play groups.

Predictors of success

What if you’re not so lucky? Maybe you already missed your puppy’s learning period, either because you weren’t aware of the importance of socialization, or because you adopted a pre-owned older dog. If this just meant that the other dogs wouldn’t play with yours on the playground, it wouldn’t be a big deal. But the most common behavior problems manifested by a dog who is poorly socialized with other dogs are fear and aggression.

Is she doomed to a life of isolation from other dogs because she responds intensely and negatively when she sees other dogs, or because there have been incidents of aggression when you have allowed her to play off-leash with others? Not necessarily. The following factors will be key to the success of a rehabilitation program for your dog:

1. How old is she? The younger she is, the better the prospects for rehabilitation. The older she is the more likely that the behavior has been happening for a long time and is a deeply ingrained habit.

2. How intense are the fights? The more serious the intent to do harm, the more difficult the behavior will be to change, and the more at risk you are (and other dogs are) when a fight does occur.

3. How capable are you of preventing fights? If you cannot control the environment to prevent her from getting into fights while you work to correct the behavior, chances of successful rehabilitation are low. If the kids leave the gate open and she gets out, or if you aren’t willing to curtail your off-leash walks and she continues to get into fights, she is reinforcing the undesirable behavior far more effectively than you are working to change it.

4. What are her breed and temperament predispositions? A submissive young Beagle whose occasional bouts with other dogs are triggered by fear and defensiveness is easier to rehabilitate than a poorly-socialized but dominant Pitbull, Rottweiler, or Akita with a history of violent encounters.

5. How much time are you willing to dedicate to changing your dog’s behavior? This is not an easy fix. Successful aggression behavior modification through counter conditioning and desensitization takes time and patience. Beware of any trainers who offer to fix an aggression problem overnight. Chances are they are likely to use coercive techniques that may drive the aggression underground temporarily but not truly change the dog’s mind-set about other dogs. You must be willing to invest a significant amount of time and effort, maybe even money, if you want to succeed.

Remedial socializing

The more positive answers you had to the above five questions, the better your chances are of ending up with a dog who “plays well with others.” If the problem is still in its embryonic stages you might be able to accomplish the desensitization and counter conditioning on your own. If the problem is more serious, you might want to make use of the services of a competent professional who uses positive methods to work with aggression problems. You will need to be realistic about your goal. Most dogs can be taught to walk calmly on leash around other dogs. Some will eventually be safe off-leash around other dogs, but not all.

Caveat: If at any time you don’t feel confident in implementing the next step of the following training program, you should seek professional help. Similarly, if you feel you are not making progress, or if your dog’s aggression or fear reaction is triggered frequently, look for a trainer to help you. Some trainers offer group classes specifically for dogs with aggression and socialization problems. (See “A Class of Their Own, February 1999.)

Step 1: Counterconditioning

You want your dog to think that being around other dogs is a wonderful thing, not something to be feared. Start by finding a location where you can control the distance between you and your on-leash dog and other dogs in the vicinity. A training class in a park is perfect – you know the dogs will stay in their class location and you can position yourself as far away as necessary. Another potential location is a large parking lot outside a pet supply store.

Find the distance that is far enough from the other dogs that yours doesn’t feel threatened. Setup a lightweight lawn chair (or sit on a park bench) and hang out there for at least 20 minutes. If there is likely to be canine foot traffic passing by, set up signs politely asking people to keep at a distance with their dogs because you are training yours. DO NOT do this in a location where loose dogs are likely to run up to you.

While you are sitting in your chair, toss your dog a steady stream of the most irresistible treats you can find. Take a huge supply with you so you don’t risk running out. Right now, she is conditioned to think that dogs are dangerous, something to be feared. By pairing the presence of other dogs with extra-yummy food, we can counter-condition her to think that the presence of other dogs is a good thing.

At this point, don’t wait for “good” behavior or pair the food with a reward marker such as a Click! or a “Yes!” We are not trying to train a behavior, we are just trying to change the way her brain involuntarily reacts to the presence of other dogs.

Note: Many dog-aggressive dogs will get so tense and wound up over the sight of other dogs that they will ignore your usual treats. This generally means two things: First, you also might have to work a little harder, or be a little more creative in your search for irresitable treats. Then, if especially yummy treats such as pieces of hot dog, meatballs, ham, or smelly cheese aren’t working, it’s a sign that the situation you have built is still too stressful. Increase the distance between your dog and the other dogs until he will take the treats, or consider finding an entirely different, even less stressful environment in which to work.

Also, some dogs will become so stressed by the mere sight of distant dogs, that they will forget their usual treat-eating manners and snap at the treats, endangering the treat-feeder’s fingers! Rather than put yourself in a position where you might feel compelled to verbally “snap” back, toss the treats on the ground in front of the dog. Or, if he’s too preoccupied with the other dogs and doesn’t notice the treats on the ground, wear gloves when you hold the treats near his muzzle! Remember: you want this to be a pleasant experience for the dog. Don’t “correct” his lapses in behavior at this point; it will only confirm his negative feelings about other dogs.

Step 2: Densitization

Desensitization is the process of gradually increasing the intensity of the stimulus that causes a reaction. It often goes hand in hand with counter conditioning. When your dog is eagerly looking forward to her trips to the park, very gradually start moving your chair closer to the training class – or other controlled source of dog presence – until you can sit next to the class and watch without a negative reaction from your dog.

The speed with which you do this will vary, depending on your dog’s response. If she starts acting uneasy when you move five feet closer, you may need to move in one-foot increments. If she is totally sold on the concept of “treats + other dogs = great stuff,” then you can move more quickly. You will still shower her with treats to continue the counter conditioning. You can also, at this point, Click! and reward specific good behaviors, such as a tail wag or happy glance at you when she sees another dog. The reaction we are looking for is, “Cool!! There’s another dog!!! Where’s my treat?”

Step 3: Interacting with others

If and when you get to this point, find a friend with a very calm, easygoing dog, and introduce the two off-leash, in an enclosed, controlled, neutral environment. Many dogs will fight on-leash and be perfectly fine off-leash. This is due in part to something we call restraint frustration (when the frustration of being restrained by the leash raises the dog’s level of arousal, making a fight more likely) and in part to the fact that the owner’s control of the leash inhibits a dog from displaying normal body language signals.

Your dog should now be relaxed and happy when other dogs are around. Let her see the other dog with both dogs on leash, and if her reaction is positive, release both dogs and let them greet each other.

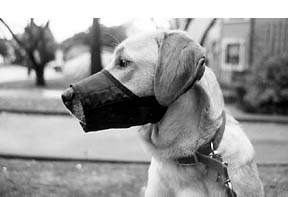

Note: We suggest that you put soft nylon muzzles on both dogs before releasing them for the first time, as an added precaution. Both dogs should be conditioned to wearing the muzzles prior to meeting, so the extra equipment doesn’t add stress. If there is a scuffle with muzzles on no one will be hurt, and you can give them a bit of time to work through the disagreement. If it doesn’t resolve itself after 10-20 seconds then break it up and remove the dogs.

This first meeting should be relatively short. You want to end on a high note so your dog goes away with a positive experience. It is important that you remain calm during this interaction and that any verbal communications with your dog are done in a relaxed tone of voice. This is not easy to do when you are wound tight in anticipation of a possible fight, but any tension in your body or voice will be transmitted to your dog, and increase her level of tension.

Assuming positive results from the first interaction, schedule several more of gradually increasing length. Meanwhile, seek out people with dog-friendly dogs, people who are willing to participate in your training program. When you find yourself relaxing while your dog plays with her first canine friend, it is time to introduce her, one-at-a-time, to other play partners. Once she has several congenial friends you can try a threesome, then gradually increase the size of the playgroup.

Your dog’s reaction to the increased levels of arousal in larger groups will help you decide if she will ever be ready for off-leash play at Carmel Beach, or if discretion dictates that she restrict her recreational activities to pre-screened pals. Whichever you decide, she will have come a long way from where she started, and be able to reap the physical and mental benefits of interactions with others of her own kind.

-By Pat Miller

Pat Miller is a freelance author and a professional dog trainer in Fairplay, Maryland.

I have two mixed Rotweiler/Ridgeback females. They are 100 lb. litter-mates, from my city shelter, where they were born. They were brought-up (by me) with little kids all around them, and they are faithful guardians of our daycare and our own family. They can be used as pillows for kids watching TV, and can be savage when coyotes jump the fence. They are easy to train and they are lovable companions for life. They are very alert and protective, especially of the kids. They love dog beach and they are great walking in crowds, and with other dogs that are stable and behaved. Occasionally, when viscous dogs come to the beach they often become victims of the sister act, and are reminded of their manners. Great dogs that listen to all commands, even from the kids. We really have come to rely on them.