Play is a widespread feature of social animals. Humans play. Dogs play. Maybe our shared need for and love of play is part of what strengthens our desire to share our lives with dogs. We play together with toys and invent enjoyable games. Many of us make a point to incorporate toy play and fun interpersonal play into our training programs, offering an exciting bout of tug or an opportunity to retrieve a prized ball in exchange for a correct response to a cue.

Used in a very specific way, play also helps shy and fearful dogs learn to work through and overcome fear and anxiety, often in cases where more traditional positive-reinforcement methods – attempts to counter-condition triggers (“scary things”) with the use of food – have been less successful.

Amy Cook, Ph.D., a Certified Dog Behavior Consultant, has been training dogs for 30 years and has specialized in working with shy and fearful dogs for the past 20. She first began exploring the therapeutic value of play for shy and fearful dogs as part of her doctoral work in psychology, where she realized the stark differences between therapeutic approaches to addressing fear and anxiety in children and how positive-reinforcement dog trainers typically addressed fear and anxiety in dogs. In exploring therapeutic approaches to traumatized children, Cook wondered if a similar approach might work for dogs.

“It got me thinking,” Cook says. “When we have a traumatized 4-year-old child, what do we do with them? Do we lean on classical conditioning to make new associations? Sure, that can be there, but there’s so much more to pull from in the human therapy model than what we were pulling from with Skinner and Pavlov as dog trainers.” Cook began exploring the many ways child therapy often incorporates playful, fun games and nurturing activities to communicate love, joy, and safety to a traumatized child.

Not long after, Cook formulated the concepts she found most effective for rehabilitating frightened dogs into Play Way.

PLAY WAY IS DIFFERENT

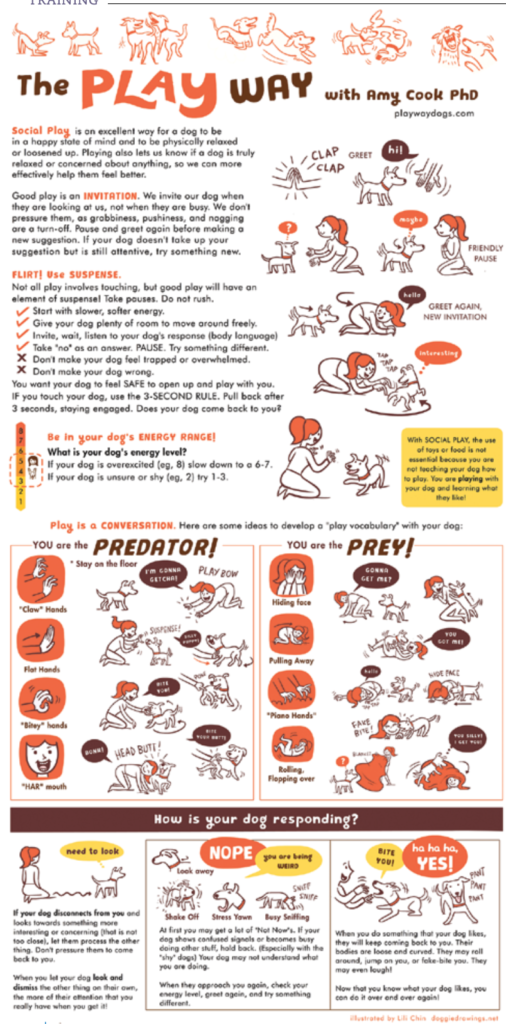

The Play Way incorporates play in a carefully nuanced manner in order to help shy and fearful dogs overcome their issues in order to live a happier, less-stressed life. But the “play” used in the Play Way is different from what many people likely think of when asked to play with their dog.

“In my system, the dog leads most of the play,” explains Cook. “I may not prod or nag or insist. I may only invite. If the dog responds with, ‘Yeah, I’d love to do that,’ then great. If the dog says, ‘No thank you. I’m busy. I’m sniffing. I’m looking at something,’ that’s okay, too. I want the trainer to communicate her availability to play, but it’s equally important to respect the dog’s answer.”

Cook says that’s the hardest part. Especially in cases where the trainer is used to aiming for constant engagement during training sessions, eager to call the dog’s name or otherwise prod for attention the instant he becomes distracted and looks away.

“We’d never dream of doing that in our interaction with other humans,” says Cook. “If you were on the phone and I wanted to talk to you, and you said, ‘Give me a second,’ I’d need to give you that time. I wouldn’t grab the phone, hang it up and say, ‘Hey! Hang up the phone! I have money, take it, let’s talk!’ The Play Way is a lot more about how interactions happen between people. I’m asking handlers to explore this space where the dog gets to decide if they want to do this.”

Giving the dog equal footing in the decision-making process is just one key aspect of the Play Way. How one plays is the other, along with teaching the dog to “look at and dismiss” potential triggers (this is described in “The Play Way, Step by Step,” on page 21).

For most people, the most challenging part of learning the Play Way is learning how to play in this manner. Play Way play is not about overly excited, high-arousal play. It’s about developing a consensual, relaxed yet playful interaction between dog and human that gives both parties permission to be silly and simply enjoy the moment. High-energy, aroused play definitely has a place in Cook’s toolbox. It’s super fun, builds and maintains arousal when needed, and is great for building anticipation and reinforcing trained behaviors. It’s just not the goal in the Play Way.

Tessa Romita of Stoneridge, New Jersey, chose a 4-month-old Coonhound puppy, Molly, from her local shelter because she seemed mellow. As she later learned, Molly’s outward appearance of “mellow” was masking a very anxious and reactive dog.

Tessa struggled to integrate Molly with her resident dogs. Molly frequently lashed out if they got too close to her or items she perceived as hers. Tessa’s resident dogs, all smaller than Molly, were always walking on eggshells, with no real idea how to peacefully coexist with their new canine housemate. Outside the house, Molly was a mix of independent, occasionally confident, and often fearful. Life was a complex maze of management strategies.

Tessa did everything right. She enrolled in a well-respected positive-reinforcement puppy class and diligently tried to help Molly. As Molly transitioned from puppyhood, to adolescence and into adulthood, Tessa continued working with trainers in an attempt to make life less stressful for Molly, and by extension, for the rest of the family. While they made some progress, eventually each of the trainers came to the same conclusion: Things were as good as they were likely to get. There was nothing more to be done. Molly’s world would need to be small.

“Then I took Amy’s class and it was a game-changer,” Tessa says. “I tear up even thinking about how this journey started for us.” For Tessa and Molly, strengthening their relationship through therapeutic play was transformational. In giving Molly the space to accept or decline invitations to play, she learned she had a choice, and in being given that choice, her confidence grew. She became more relaxed. “It’s so powerful to see how Molly learned she can be out in the world and not need to scan and worry about what could happen; instead, she trusts me and enjoys being out.”

The situation even improved between Molly and Tessa’s resident dogs. Whereas management used to be a big part of their daily life, the dogs now enjoy loose, relaxed social interaction. “It took time, but it’s beautiful. They’re friends now,” says Tessa.

Molly still has times when she struggles with anxiety, but overall she’s more relaxed, more confident, and sometimes even downright silly. “I’ll have these random moments where Molly does something she’d never do before, like suddenly go wading through a creek when she used to be afraid of water, or not care about an alarm going off when she’d been painfully sound-sensitive,” Tessa says. “I’ll email Amy in amazement and her response is always, ‘Play is magic.’”

THRESHOLDS

Taking the time to develop a conversational, give-and-take social play relationship is important because in rehabilitating shy and fearful dogs, the dog’s ability to engage in this manner serves as a barometer for how a dog is feeling.

Threshold is a phrase that comes up a lot in work with fearful dogs (and dogs who exhibit aggressive behavior, too, which makes sense because a lot of aggression is directly traced to fear). Threshold is loosely defined as the moment when a dog crosses from one emotional state to another. In the specific context of fearful dogs, a dog who is just “under threshold” is in that emotional sweet spot where he’s aware of the presence of the trigger (the “scary thing”) but not feeling at all threatened. Once he’s tipped into a fearful state (“over threshold”), the fight-or-flight hormones (adrenaline, cortisol) may kick in, making it hard for him to think, learn, remember, and respond like a more “normal” dog.

When working with fearful dogs, the ability to keep the dog sufficiently sub-threshold is paramount to the training success. But keeping a dog under threshold is often easier said than done. Real-world variables can change on a dime, especially if one hasn’t gone to great lengths to carefully set up a controlled training session. And a stressed dog is not in the proper mental state to learn he is safe in the presence of the trigger.

“When I first learned about positive reinforcement-based dog training, the general wisdom was that as long as the dog is eating, he’s under threshold,” says Cook. “That might be a reliable indicator for some dogs, but it’s far too unreliable for me with the degree of under threshold I’m aiming for. After all, many dogs can eat or tug on a toy while stressed.”

NOT THE USUAL COUNTER-CONDITIONING

Many trainers turn to classical counter-conditioning to help rewire how the dog’s brain reacts to scary things. But Cook’s method follows more of a human therapeutic model.

Rather than use food in an attempt to reprogram how the dog feels in specific situations, her goal is to help the dog naturally achieve an emotional state where he can comfortably evaluate a situation and come to his own conclusion that there’s nothing to worry about. It’s similar to how a skilled human therapist guides a person through a healing process in such a way that the client discovers the answers herself.

“It’s about giving the dog the chance to self-soothe from a place of entirely established safety, and where they’re already feeing relaxed. Now they have a chance to gather new information and I don’t have to tell them what specific response they should be having. I’m not saying, ‘You’re right, there’s a stimulus (the scary thing) and now I’m going to give you something (food) to influence you directly.’ Instead, I can say, ‘Go ahead and look at the scary thing and come to the very real conclusion that you are not under threat here.’”

Play helps facilitate the process. Whereas the goal of food centers around changing the dog’s conditioned emotional response (CER) to the trigger, the goal of Play Way play is to help put the learner into a better state of mind from which to fully evaluate the situation and organically realize there is no threat.

1. Learning the Language of Play Way Play. For most people, this is the most challenging part of the Play Way. This first step focuses on developing a therapeutic play style that allows for relaxed, silly, low-energy, consensual activity, where the dog is given room to say, “No thank you,” “Not right now,” or, “I’d rather do this instead of that.”

2. Location, Location, Location. Once the dog and handler have come to a mutual understanding about this new style of interaction, make sure it holds up by playing in many new, non-challenging locations, such as different rooms of the house.

3. Developing “Look and Dismiss” Using Simple Distractions. Now it’s time to introduce simple, non-worrisome (trigger-free) distractions. The “look and dismiss” part of the Play Way is about helping the dog realize he can acknowledge potentially “scary things” from a place of safety, realize it’s no big deal, and calmly dismiss the potential trigger. This starts by practicing look and dismiss with simple distractions.

The critical piece of this skill is for you to let the dog control the session; you just open the door to the possibility of play. Let’s assume your dog is initially receptive to the invitation. If she disengages for any reason – say, a blowing leaf catches her attention – let her do so. Pause, wait, and allow her to process the information. When she reorients her attention to you, simply acknowledge her warmly, and then, if her attention is still present, re-issue the calm, casual invitation to play and wait to see how she responds.

This can be tricky, as there’s a great temptation to enthusiastically react to the dog’s choice to re-orient to you by instantly re-engaging in play. But the calm, casual, re-issuing of the invitation to play, and not an enthusiastic, potentially rewarding reaction is a critical element of “look and dismiss” in the Play Way, Cook says. “You want to leave room for the dog to look back at the scary thing if she needs to. Dismissal can come in stages. If you play too quickly, you can overshadow the dog’s natural thought process.”

The Play Way is not about teaching the dog to look at triggers and then look back at you in order to earn a reward of play. Cook doesn’t want the dog to be seeking rewards, but instead, to be in a mental state that supports his ability to acknowledge the trigger’s existence and realize it’s not so scary after all, so it can be comfortably dismissed. It’s important to practice this step a lot so the dog becomes well rehearsed in looking, processing, and dismissing – all on his own, without being cued to return attention to the handler.

4. Formal Training Set Ups. Once the dog is well practiced at noticing but easily dismissing assorted non-concerning distractions in favor of engaging in therapeutic play, it’s time to introduce slightly more challenging distractions that might be of minor concern, taking care to present them at a very low level.

For example, if a dog is fearful of other dogs, one might use a realistic-looking stuffed dog placed far in the distance. If the dog worries about strange people, a helper might stand far away. Distance is important since, for most dogs, the farther they are from the trigger, the less problematic it is. The goal is for the dog to see the trigger, but to now have the tools –the ability to look and gather information from a place of safety – to process the situation and realize there is no threat. If the dog can’t easily look and dismiss the trigger, that’s key information for the handler, who then aborts the session and creates an easier training scenario next time.

Cook points out these set-ups rely heavily on the handler’s ability to control the environment temporarily in a way that avoids being ambushed by the dog’s trigger. For those everyday situations where one just needs to walk the dog through a neighborhood full of potential triggers, she recommends careful management such as keeping a safe distance from “the scary things,” along with using food in a more traditional positive-reinforcement framework such as consistently feeding in the presence of the trigger, often known as “open bar, closed bar,” to help prevent the rehearsal of unwanted, reactive behavior.

Over time, Cook says clients report a marked decrease in the amount of management needed to navigate everyday, real-world situations. Their dogs might still notice triggers, but find it far easier to dismiss them and move along.

“Dogs get really good at gathering information quickly, and from a place of calm safety, so they aren’t feeling triggered and don’t need to overreact,” she says. “It’s much easier for them to look at people or dogs and it’s like they’re saying, ‘No big deal. I’ve seen that before. We can move on.’”

WHAT PLAY WAY PLAY LOOKS LIKE

Play Way play is about social, interpersonal play, more so than playing together with toys or using food. What matters most is that the human acknowledges and adopts the conversational nature of how dogs play with each other, rather than seek to drive and control the play interaction.

Healthy dog-to-dog play has a natural rhythm. There’s a lot of back and forth. They pause. They hold suspense. They change things up. They don’t much enjoy a play partner who is being pushy. It’s not as much fun to play with someone who insists on picking the game and dictating exactly how it’s played.

“It’s a lot like working with toddlers,” says Cook. “With kids, you don’t get to decide how the game goes. It’s no fun if you decide we have to play Candyland and then you win. Play Way play is about being cooperative, improvising, and letting the dog make suggestions like, ‘I want to do this…’ or ‘I don’t like when you poke my butt with your claw hand, but I do like to play fake bitey-face with you.’”

Try play-bowing at your dog. Hide your face and encourage your dog to burrow under your hands to “find” you. Cover yourself with a blanket and do the same. Start with slow, soft energy and give your dog plenty of room to move around. Try to exude affection. Flirt! When you touch the dog, pull back and invite her to come toward you. Don’t be afraid to try new things, but don’t frantically switch from one behavior to another. Float an idea and see what happens. If your dog is used to interactive toy play or frequent training sessions, he might be confused and need time (over several short sessions) to figure out what’s going on.

PLAY WAY ADVANTAGES

According to Cook, one of the biggest advantages of the Play Way method is its ability to keep handlers honest about whether or not the dog is under threshold. That’s because many food-motivated dogs will still eat and some toy-motivated dogs can still enthusiastically tug even though anxiety is creeping in. In contrast, social play (as practiced in the Play Way) is far more fragile. Social play is the first thing to go when stress starts to creep in, says Cook.

“It’s not very robust,” Cook says. “The second a dog starts to have even a mild concern – or even a curiosity that might lead to a concern – the play stops. When that happens, you as a trainer have a clear indication of something you need to pay attention to and potentially adjust. It keeps the trainer honest about staying under threshold.

“I like things that help me counter my own biases and weaknesses as a human being,” Cook continues. “When you’re trying to get something done, you might be tempted to tell yourself it’s okay, the dog’s fine if he’s eating or tugging. I find this type of social play keeps me really honest in my assessments.”

The ability to maintain a high degree of accuracy regarding the dog’s thresholds can lead to faster results compared to traditional classical counter-conditioning protocols. It’s a heavily front-loaded effort that pays off in the end. By taking the time to slowly develop a wholly consensual, give-and-take play relationship with a dog, you gain the ability to use social play for therapeutic purposes. And in using social play therapeutically, you’re less likely to accidentally push the dog over threshold.

Also, by preventing the dog from going over threshold, he’s more likely to take consistent steps in the right direction, instead of setbacks continually causing him to take two steps forward and three steps back.

People often mistakenly refer to the Play Way as a classical conditioning set-up that uses social play in place of food to help change how a dog feels about the “scary thing.” But Cook says that’s not entirely correct. A common approach used by positive trainers working with shy and fearful dogs is to strategically offer food or toys – something the dog readily enjoys – anytime the trigger (the “scary thing”) is present, so that the dog comes to associate the scary thing with the availability of food or toys, and the newly formed association reduces the degree of concern. This is called classical counter-conditioning and it frequently works wonders.

However, with the Play Way, says Cook, “I’m specifically working to avoid a situation where the dog looks at the scary thing and then instantly play happens. Instead, I’m using play to facilitate the dog’s ability to be in a relaxed, happy state where he can comfortably assess a situation and decide for himself that he’s safe. I know Pavlov is always on your shoulder, but the focus of the Play Way is not to drive the purposeful formation of specific associations. I’m actively trying to not contribute, as a trainer, to the associations being made by the dog.”

For more information about the Play Way, visit playwaydogs.com or check out Cook’s online course, “Dealing with the Bogeyman – Helping Fearful Reactive and Stressed Dogs,” offered via Fenzi Dog Sports Academy, fenzidogsportsacademy.com.

MUTUALLY RESPECTFUL TRAINING

Here’s an aspect of play therapy that is less commonly seen in other dog training methodologies: Being “present” – sensitive and respectful of the dog’s needs – is an integral component of the Play Way.

“It’s not about coming in with a plan and saying, ‘I’m going to make this specific thing happen to influence you to feel a certain way,’” Cook explains. “I’m sensitive and listening to my learner. It enriches all of my training to consider a space where I’m respectful of the viewpoint of my dog. I don’t think that’s something we emphasize enough in dog training.”

That’s not to say Cook suggests dogs should call the shots all the time; she knows that’s not realistic. But setting aside time to develop social play is also beneficial as an overall stress release for both shy and fearful dogs and their owners.

“Reactive dogs, shy dogs, fearful dogs – they all live a more inherently stressful life,” Cook says. “It’s hard to be routinely triggered by stressful things. We all need play, silliness, and laughter to help shake-off these types of stressful build-ups. I think, in general, we don’t really do enough to relax the dogs who spend a decent amount of time feeling an overabundance of stress compared to a more adjusted dog.”

In this way, the Play Way method can be just as beneficial to the dog and owner as a team as it is in its ability to help the dog organically work through its fears.

“When you own a fearful or reactive dog, you yourself are often stressed,” says Cook. “You’re nervous your dog will blow up at any time, and you’re worried what people will think. Maybe you’re even grieving a little bit because this isn’t what you pictured when you thought about getting a dog.

“I think it helps the human, the dog, and the partnership to have this one expectation-free space – this isolated time where you only focus on what you both can do right, where you make each other laugh and enjoy being silly together. That kind of connection can help keep you invested for the long haul in helping your dog. It can recharge the batteries in the relationship.”

As Cook always says, it’s magic!

Five-year-old Cash, a Belgian Tervuren has always been a “special dog with special needs,” explains Susanne Handwerk of Eichgraben, Austria. Susanne says he used to be anxious about strangers, leery of other dogs, and on high alert when he was away from home. Also, he’s not very food- or toy-motivated, so traditional management techniques involving food or toys are of little help. Many facets of life with Cash had become “frustrating and exhausting” for Susanne.

Finding Fenzi Dog Sports Academy and Cook’s “Dealing with the Bogeyman – Helping Fearful, Reactive, and Stressed Dogs” class changed how Susanne approached training with Cash. Whereas prior trainers insisted she work to make toys more valuable to Cash, learning the Play Way taught her how to develop new games they could enjoy together. The class also helped her better understand thresholds, and the importance of keeping Cash under threshold.

“Now I realize Cash was over-threshold much of the time,” Susanne says. “And because he was so stressed, he was sleeping most of the time at home. Everybody told me that was a good thing, but now I know it wasn’t. He was exhausted. That’s no way to live.”

Taking the time to develop a therapeutic play relationship helped Cash relax. “It helped him become less serious and to worry less,” Susanne says. “And I think it was helpful for him to realize I would listen to his signals – that a, ‘No’ would be, ‘No.’ In the beginning, he ignored most of my invitations to play, but the more I respected his answers of, ‘No,’ the more he was ready to play with me.”

Susanne says Cook’s class was life-changing in teaching her how to help Cash learn to trust her as his partner, develop confidence and become resilient. While he still has some challenges, he’s quicker to acclimate to new environment, can successfully work around other dogs most of the time, and generally ignores strangers.

“The Play Way helped Cash lighten up and learn I would listen to him and support him,” Susanne says. “And it helped me lighten up because I feel like I’m able to help him.”

As a trainer, Play Way, is the most exciting concept I have come across in a decade of training. Amy Cook has really opened my eye’s to a new type of therapy for fearful and anxious dogs besides the typical use of food.

I have been having incredible success using PlayWay with my clients dogs and helping these dogs find their joy again. I am seeing so many subtle signs that were missed when the dogs were easily just eating food but were still mildly anxious. I am finding the dogs are responding in a whole new way. I have a lot of laughing dogs to work with now:)

Thank you Amy!

So interesting! My morning yoga sessions often turn into these kinds of play sessions with my dogs. Which makes total sense when you compare the yoga poses to dog play postures. My fearful boy goes from zero to over aroused when playing. Do you have any tips for easing him into this? I’m still working on take it and leave it so we can safely play tug

How I wish I could have read this artical in the winter of 2020. It would have saved so many hours of sadness.

I had never experienced a puppy that expressed such constant stress and fear. After hours of early socialization and 10 weeks fo puppy classes we were at a complete loss.

Our puppy’s trainer was extreemly patient with us in class, even though our pup did all the training exercises well and willingly at home, she would struggle to even enter the training building, but eventuality would

get into class, then curl up on her mat, and go to sleep. No tail wag, no vocalization, little or no interaction with other pups.

Then with the advent of covid-19 trips out and about stopped.

I’ve continued with training at home. We also have a mellow 3 year old GSD male who she bosses around and plays with. We accidently discovered the game of Peek-a-Boo and found a new dimension to our girl. She loves to play with us, too. Fetch is her newest game. She nuzzles with the outdoor cats and enjoys walking with me anywhere on our property but turns into helicopter mode if I take her out of the front gate.

I will definitely utilize the poster attached in this artical.

We are resolved to accept her as she is but learning g is life long for her and us. Thankfully she is not aggressive but is very affectionate. Thank you for your awesome artical!

Great article. Can’t wait to try on my reactive, very busy, sweet Aussies.

Nice article I’m going to try all that in my beautiful,sweet baby..

Is there any way I can get a copy of the chart? It prints very tiny. I just adopted a young feral dog and could really use this in readable format; I don’t keep the issues after I have read them for, and generally look online, this is one I could really use!

I have an extremely fearful dog named Phoebe, rescued from a puppy mill where she was a breeder her entire life. Now at 6 she can finally enjoy life, although she is still very fearful of me. I have had her 4 months and have not yet been able to touch her and even put a collar on her. I’d love to try this concept but being that my girl was never socialized, she doesn’t even care for treats in any way, breakfast and dinner time are okay as in she will eat eventually. It doesn’t seem there is any one trigger that frightens her, but anyone getting close to her and interacting with her that scares her. I’m confused about how to invite to play in the case that a dog doesn’t understand toys, treats, or traditional play and doesn’t want to interact. She does seem interested in whatever I’m doing and will follow me around but only at a distance. any help would be amazing! I just want to start seeing her enjoy life instead of hiding under the bed.